Over 120 crime fans turned up for Sisters in Crime’s 13th Annual Law Week event on Friday 17 May, Stalking, Trolling and Cyber-Bullying, organised in partnership for the fourth year running with the Sir Zelman Cowen Centre, Victoria University.

Special thanks to Professor Kathy Laster and her wonderful team for helping make this all happen. Thanks also to the Victoria Law Foundation for its sponsorship.

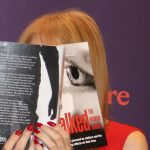

Wendy Tuohy, a journalist with The Age, compered the event with great sensitivity. What the three authors Ginger Gorman, Emma A Jane and Rachel Cassidy had to say about cyberhate shocked even the most seasoned true crime aficionados. Rachel does not allow photographs for obvious reasons.

A podcast will be coming but meanwhile here is the digital article published on The Age and Sydney Morning Herald the night before. It didn’t get much traction as the announcement of the death of former Prime Minister came 40 minutes later. It also appeared in hard-copy versions of the two papers on Sunday 19 May.

_______________________________________________________________________

Eighteen months since the dawn of a movement demanding an end to women being viewed as prey, prominent women’s safety advocates say measures to protect Australian women online remain “woeful”, and cyberstalking, trolling and harassment remain rampant.

#MeToo may have made men in prominent roles more wary of crossing real world boundaries, but according to advocates Ginger Gorman – author of the 2019 book Troll Hunting: Inside the world of online hate and its fallout – cyber-harassment researcher, Dr Emma Jane and Stop Stalking Now Foundation’s Rachel Cassidy, women are still being targeted at “their weakest point”.

Ginger Gorman believes social media companies have been woefully slow to enforce protections for women, and police are also lagging in their response to allegations of online crimes against women, including serious online harassment.

Ginger Gorman believes social media companies have been woefully slow to enforce protections for women, and police are also lagging in their response to allegations of online crimes against women, including serious online harassment.

“In terms of policing, it’s like domestic violence was 30 years ago – they think it’s a private matter. They don’t understand the real-life harm it does, the relative legislation or how to investigate crimes like this. They don’t have the training or resources to deal with it,” says Canberra-based writer, Gorman.

“As for the social media companies, governments urgently need to legislate a duty of care so they have to keep us safe. Because they clearly aren’t going to do this on their own.”

Gorman commissioned 2018 research from the Australia Institute into the incidence and impact of trolling. The national survey found 44 per cent of women and 34 per cent of men had experienced some form of online harassment, but while men experience “more abusive language about religion and ethnicity”, and about political beliefs than women, women were still enduring more online abuse in every other category.

“Women experience harassment in ways that are far more sexual, violent and sustained. These differences aren’t by accident. They are to do with what are considered to be the ‘weakest’ points of men versus the weakest points of women. Trolls are sadists – they attack where it hurts the most.”

Digital harassment researcher and University of New South Wales senior lecturer, Dr Emma Jane, says the advent of the #MeToo movement has triggered more activity among online abusers.

Digital harassment researcher and University of New South Wales senior lecturer, Dr Emma Jane, says the advent of the #MeToo movement has triggered more activity among online abusers.

“Unfortunately, #MeToo has been a magnet for trolls (for want of a more precise term).

An online threat like, ‘I’m coming to rape you and your children’ is likely to land very differently when it is sent by a man to a woman.

Attacks on women online are highly gendered, unlike attacks by men on other men. “An online threat like, ‘I’m coming to your house to rape you and your children’ is likely to land very differently when it is sent by a man to a woman (than were it sent by a man to a man).

Rachel Cassidy, CEO of Stop Stalking Now foundation and author of the new book Stalked – The Human Target, says there is still often a lag time between law enforcement and the justice system “catching up to the current cohort of perpetrators” who use technology to commit cyberstalking.

Rachel Cassidy, CEO of Stop Stalking Now foundation and author of the new book Stalked – The Human Target, says there is still often a lag time between law enforcement and the justice system “catching up to the current cohort of perpetrators” who use technology to commit cyberstalking.

“One forensic psychologist I interviewed said there is a new wave of very savvy, sophisticated stalkers using various forms of technology to their advantage to aid their pursuit of their target,” she said.

“As we know young, people are committing suicide from cyberbullying and cyberstalking and at times the perpetrators also solicit others to join their pursuit of the target; it’s called stalking by proxy, and can lead to the target becoming totally overwhelmed by a vigilante type of situation where they feel a number of people are attacking them and then a feeling of helplessness and hopelessness can take over.”

She said cyberstalking was “very rampant in the community”, despite the awareness raised of harassment by #MeToo, and “the community at large should be more aware and involved” in combatting attacks.