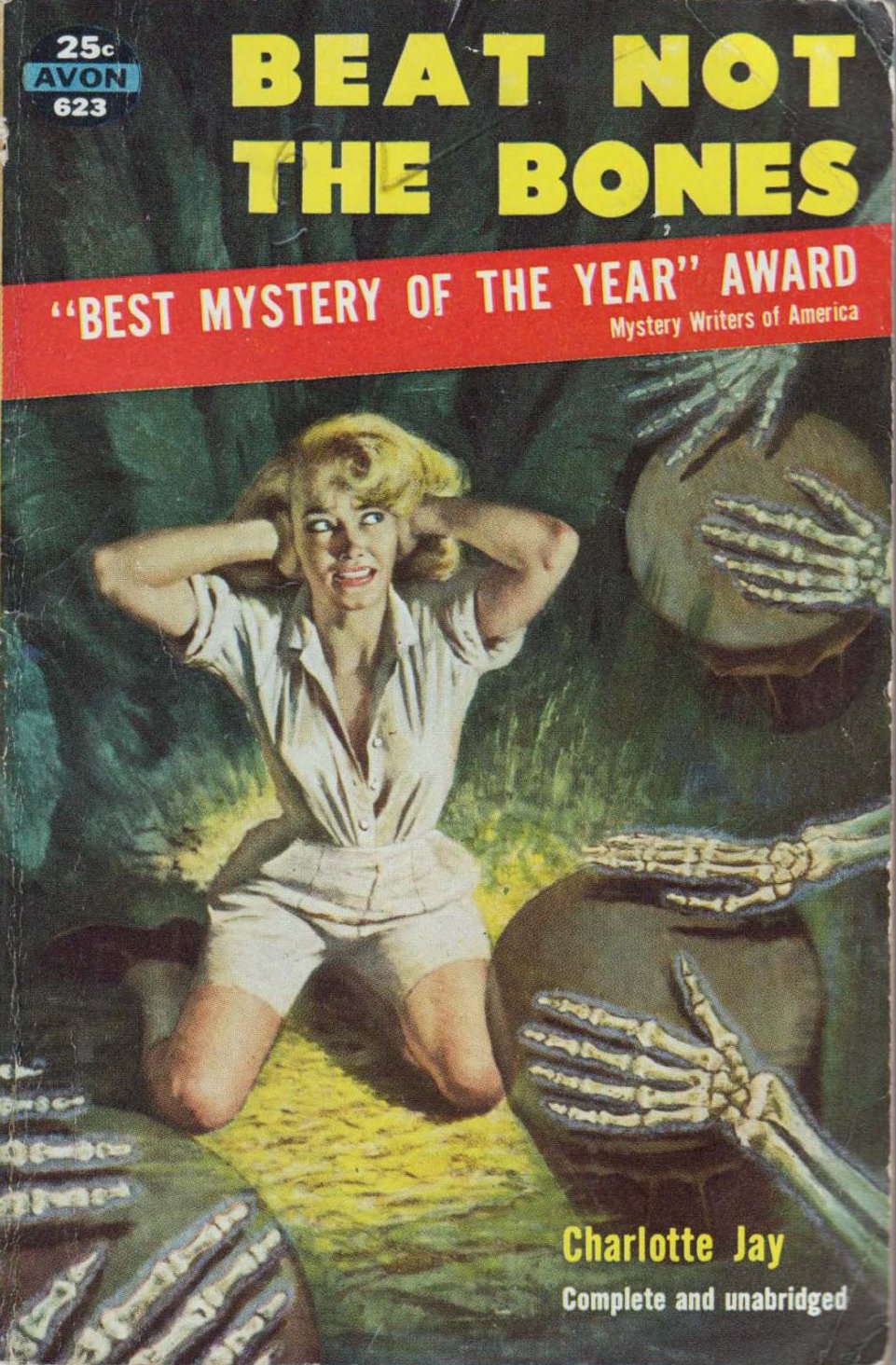

In 1992 Sisters in Crime co-convenor, Carmel Shute, was fortunate to interview pioneering Australian crime writer, Charlotte Jay, on the eve of the re-issuing of her 1952 novel, Beat Not the Bones, which had the rare distinction of winning the inaugural Edgar Allen Poe Mystery Writers of America Award. (Raymond Chandler won the following year.)

Carmel, along with another Sister in Crime, Katherine Kovacic, will be in conversation with Emeritus Professor Chris Browne about Jay at the Melbourne Rare Book Week, 6.30pm Wednesday 10 July. Click here to book and click here for the video interview with Carmel about Jay (skip the first couple of minutes where she is very nervous!!)

Carmel’s interview was published in the Australian Women’s Book Review, Vol 4 No 4, December 1992:

Charlotte Jay is the pseudonym of Geraldine Halls, a crime writer and novelist born in Adelaide in 1919 and still going strong. She returned to Australia fifteen years ago after living in many different countries.

Carmel Shute from Sisters in Crime spoke with Jay when she visited Melbourne recently to promote the re-issue by Adelaide’s Wakefield Press of her award-winning work, Beat Not the Bones.

Carmel: You’ve been writing crime for over forty years and Beat Not the Bones won the first Edgar Allen Poe Mystery Writers of America Award in 1953, so do you find it surprising that you are not better known in Australia, despite having lived outside the country for so long?

Charlotte: I had a name in America and England. I wouldn’t have thought my books would have much appeal here, except possibly Beat Not the Bones might have attracted more attention. New Guinea is very close to us and we were administering it. [The Voice of the Crab (1974) is also set in New Guinea.]

Carmel: I have just finished reading Beat Not the Bones and I find it a powerful and terrifying story. I think it works at different levels – both as a mystery and also as a story of a woman’s self-realization. Do you see it as a woman’s rite of passage?

Charlotte: It’s interesting you should ask me that because an awful of what a writer puts down she doesn’t necessarily know what she is doing. And I can see it was about the development of a woman and her self-realisation. When I wrote the book, I didn’t have that intention at all.

Carmel: What was your intention?

Charlotte: My intention was to scare people ad get a lot of readers.

Carmel: And did you succeed?

Charlotte: Internationally it was a success, particularly in America.

Carmel: The picture you paint of whites in Marapai (Port Moresby) and the colonial administration is a damning one. Was your depiction of racism and colonialism a cause for comment in 1952 when the book was first published?

Charlotte: It didn’t cause any at all, nor was any intended. I admired the Australian administration of Papua New Guinea. I thought they did a jolly good job. You take two characters and they are corrupt or bad – you’re not damning the whole thing… But you have to have a story and it’s only an adventure story. You’ve got to have goodies and baddies.

Carmel: Your very first crime novel, published by Collins in 1951, is The Knife is Feminine. It’s a very intriguing title. What is it about?

Charlotte: It’s about a man, a very big, ruthless industrialist, who has a lovely daughter. He is trying to insidiously introduce a kind of fascism into his factories. He uses his daughter as a weapon against the man she loves and who is trying to attack this idea, trying to expose it. But, once again, it is an adventure story, an entertainment.

Carmel: Was winning the Edgar Allen Poe Award a highlight of your literary career?

Charlotte: It wasn’t at all. To begin with, I didn’t know what the award was. When I found out, I just couldn’t believe that my book had won an award. I think I now understand why I did. It was simply because it was breaking new ground. There was the school of American writers writing about the backstreets of New York. In England there was Dorothy Sayers, Agatha Christie and people of this kind. I took the crime story out of that arena and put it in the jungle, into Rider Haggard country. That struck people as refreshing.

Carmel: Raymond Chandler won the second Edgar Allen Poe Award with The Last Goodbye. How do you see yourself in relation to Raymond Chandler and the American school of hard-boiled crime writing?

Charlotte: I don’t see myself as having any relation to them at all. I think that if talk about me and Raymond Chandler, you’re talking about a horse and a swan, or a pear and an orange. He was sitting around producing crime books and I was writing adventure stories. There is nothing in common between them. My writing was largely derived from Gothic writing from England and America… Edgar Allen Poe himself [and] going right back, The Woman in White, Le Fanu, Uncle Silas… It had nothing to do with Chandler or the English school.

Carmel: Why did you turn to crime writing in the first place?

Charlotte: It was simply because I wanted to be published. I felt I had a certain gift for crime writing – horror, mystery – because my father, who influenced me greatly in my reading, had two little books, one called Crime and Detection and the other called Mystery and Imagination. I adored those books. I used to read them again and again. I adored being frightened by them, I thought that’s what I’m going to do. I am going to frighten people.

Carmel: Was crime writing an unusual occupation for an Australian woman in the early fifties?

Charlotte: You do what you feel you want to do. If you feel you have a gift, you pursue it. I suppose I must have felt that I had a gift. The alternative for me was to on working as a shorthand typist in an office [which she did for twelve “terrible years”].

Charlotte: You do what you feel you want to do. If you feel you have a gift, you pursue it. I suppose I must have felt that I had a gift. The alternative for me was to on working as a shorthand typist in an office [which she did for twelve “terrible years”].

[Because Charlotte Jay’s husband worked for UNESCO, he was posted to many different countries and she travelled with him. These experiences enabled her to set her stories in Pakistan, Thailand, India, France, and the Trobriand Islands.]

Carmel: During this whole period, was writing your main activity? Did you have any other work, children?

Charlotte: No, I didn’t have children and I didn’t have any other work. It was ideal. In that set-up, you did not have a very cluttered social life. My husband was not a man who wanted a lot of social life. So he would go off to work in the morning and I would stay at home and write my books. Now it’s much more difficult because, coming back to my home city [Adelaide], I do have a social life.

Carmel: What about the role of women? In Beat Not the Bones, the central character is a woman on a particular quest: to find out who murdered her husband in the jungle of Papua New Guinea. Do you other books have a strong woman-centred theme?

Charlotte: One is centred around the crack-up of a marriage that happens to the woman for the same reason… their inability to absorb the culture shock, which is India, which their husbands can absorb… In two of my books, the narrator is a man. One of the best ideas I had… was about a man in England who was blind in one eye and had an accident which threatened his second eye. It’s called The Fugitive Eye [which was made into a film starring Charlton Heston].

Carmel: Did you find it had to write a central character with a male persona?

Charlotte: No, I don’t think so and, after all, men have portrayed some extremely good women – look at Becky Sharpe, look at Moll Flanders. It’s only a projection of imagination. After all, I’ve never been in a jungle, It’s a completely imaginary jungle [in Beat Not the Bones].

Carmel: Why did you choose the pseudonym Charlotte Jay?

Charlotte: Jay is my family name – and I think I chose the name Charlotte because it is a literary name.

Carmel: You’re currently writing another novel. What’s the novel about and who’s going to publish it?

Charlotte: I feel a bit suspicious [talking] about something which isn’t published, hasn’t been seen by a publisher and could be rejected. So I’ll simply say it’s set in Australia – mostly.

Carmel: Are you reading any of the modern women crime writers?

Charlotte: I’m not but I think I shall. I’m also not reading many contemporary novels. Frankly, they disappoint me. They can be beautifully written, but many of them don’t tell a story. They don’t have a structure. They don’t even entertain. These things, to me, are absolutely essential. You must have a story. You must have structure and you must write something which attacks a moral problem or some major issue. A lot of contemporary novels seem so narcissistic. They’re little slabs out of an author’s life, but they’re not addressed to their readers but to themselves.

Carmel: Do you have any advice for young women starting off on a life of crime fiction?

Charlotte: I’d say, first of all, that if you’ve got a gift you’ve got it. If you haven’t, there’s no good… If you’re going to be a writer, you should take enormous pleasure in writing, to be determined to give pleasure, not just for yourself, but to readers. You must tell a story. That goes for any novel really.