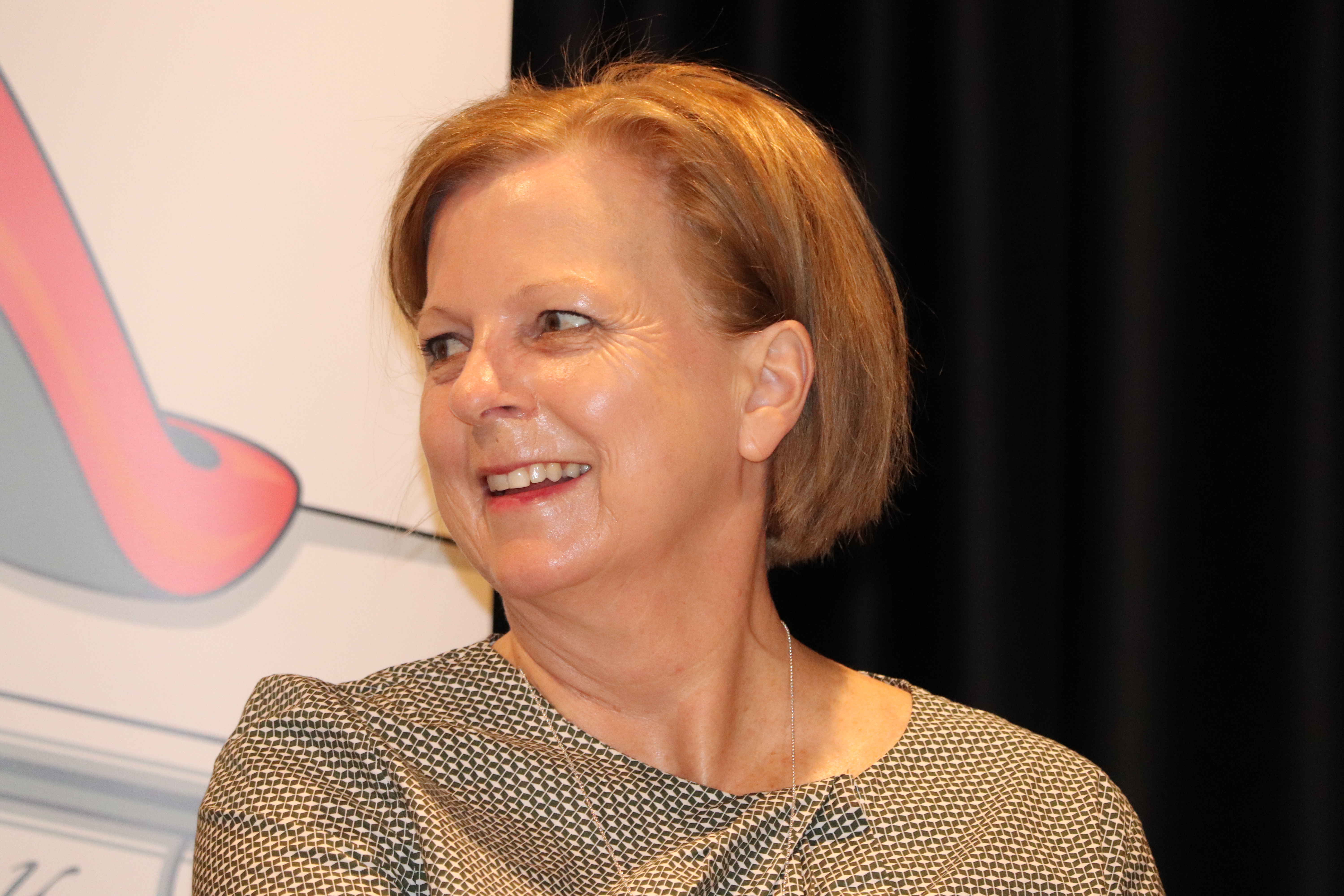

Joanna’s latest book is The Slipping Place (Impact Press, 2018) and she spoke about her literary trajectory with Robyn Walton, Sisters in Crime’s Vice-President.

Hi, Joanna. First let’s talk about your crime and mystery writing for young adults. In 2005 you won Sisters in Crime’s Davitt Award for Best Young Adult Novel for Devastation Road. In 2018 Devastation Road was re-released, and you have a sequel published this year plus a third story in the series on the way. Can you tell us a little more?

It was such an honour and an encouragement to be granted that award and it really did keep me writing over some quiet years!

With Devastation Road I set out to write a fast-paced, Agatha-Christie-style mystery that would appeal to today’s young adult readers. In the process of writing I found I had written scenes where two fifteen-year-olds find the body of a friend. Then later they speak with the parents of two dead girls. So, I found I was including some short passages about young people struggling with the largest of truths and mysteries – human mortality – and starting to recognise deep, deep grief.

The book is still primarily an entertaining clue-puzzle, but it has heart and depth and adults are enjoying it.

I also found I couldn’t leave Matt and Chess alone. I am massively fond of these two kids now. They had come a long way and they had more to learn. The Elsinore Vanish is a new take on the locked room murder mystery – a murder that seems impossible, which challenges Chess’s reliance on cold logic. It’s about conjuring and magic and is set in Beechworth in country Victoria.

Finally, Chess has her own personal story which I really wanted her to work through. When she was very young her mother died, and no one will tell Chess what happened. Naturally this is something that has set the tone of her whole life. After she has successfully solved two mysteries, Chess realises it is time to find out what happened to her mother, and of course Matt helps her. This happens in Evermore, which will come out late in 2019.

Now to The Slipping Place. It’s for an adult readership, perhaps an older-adult readership. Your protagonist, Veronica, is aged 58, and as readers we spend a lot of time with her and her peers. I found the lifestyle details and characters credible and engaging. Any comments?

Now to The Slipping Place. It’s for an adult readership, perhaps an older-adult readership. Your protagonist, Veronica, is aged 58, and as readers we spend a lot of time with her and her peers. I found the lifestyle details and characters credible and engaging. Any comments?

I love writing about older women, and I think they make great detectives. I’m a bit reluctant to claim we have ‘wisdom’, whatever that is, but I think older women bring richness – depth of experience and deep and nuanced emotions and commitment to things.

Veronica is very human and fallible and sometimes blinkered and sometimes ineffective. But she has great strength and determination when it comes to protecting her family. That is what I admire in her.

Veronica, Lesley and Judith are not entirely sympathetic characters. They are complex. Maybe that’s the quality that fascinates me. Does that sound fair? Older women are complex.

I’m not sure that Veronica is really a detective at all. I wanted to write about a woman struggling with mysteries within the circle of her own life, among the people she cared deeply about, and about different people struggling to understand life in different ways. That’s what The Slipping Place is really about: it’s a murder mystery about mystery itself.

The other adult characters belong to the generation below. They’re mostly in their twenties and come from more diverse backgrounds. How did you find the experience of creating these characters and their relationships?

Well, they are certainly very real people to me. Maybe I have written them from a mother’s perspective. The book is very much deeply embedded in Veronica’s point of view. Do you think Roland and Paul are portrayed as Veronica would perceive them? They are not perfect characters, but she sees them from a place of deep unconditional love.

At first, Veronica makes cursory judgements of the other young people – Treen, Vicky, John, Belle – but I hope as the book goes on she starts to develop deeper understanding of all of them.

Treen and Belle have terrible lives and their behaviour is challenging and sometimes hard to understand, but dreadful things happen to them and I hope they are also drawn with compassion.

The Slipping Place is a book in which no one is perfect.

The action gets going with Veronica hunting around Hobart for her wayward son, Roland. She fears he is in ‘one of his messes’ and may be trying to help ‘a child who was hurt’. Is she right to be concerned for Roland’s well-being?

Oh, I would love to leave it up to the readers to decide which of Veronica’s judgements are right and where she goes wrong.

Roland is definitely problematic. In my opinion he is well-meaning but naive, frustrating, self-absorbed and sometimes deluded. But please make up your own mind. He tries to help people in his own way. He tries to express himself with art. But as I said, I leave it to readers to judge. I love it when readers respond strongly to my characters.

And what about this young child’s wellbeing? The story raises dilemmas about who to prioritise, who to protect, who to try to help, and how to go about intervening or covering up.

One of the ideas that inspired the book is that question of how we respond when terrible things are happening within our own communities. How do we decide when to intervene? As individuals we can’t help everyone. What is our responsibility? How do we choose? These are profound questions.

But that’s too cold. If a young child is being hurt, that is completely appalling. It’s unthinkable. Imagine if we were in the room when it happened. And yet we don’t always know what to do or whether we can do anything. This is huge stuff.

When Veronica thinks ‘Roland Roland Widdershins, you can’t save them all’, that is a crucial line for me.

Roland supplies visual clues about what is happening to him and his associates. And the strange older woman sheltering him behind her bookshop talks in quotations, mostly from 19th-century literature. I suspect you enjoyed weaving in these allusions and parallels?

Oh yes, all that was definitely put in there for my own pleasure. I loved playing around with the books and looking at the Tenniel illustrations and piecing together threads about women who are sidelined, women who die and suffer simply to make the story happen for someone else.

And I love [Robert Browning’s 1855 poem] “Child Roland to the Dark Tower Came”. It’s so mysterious and powerful and such a deeply mythological figure, the brave young knight riding on without hope.

At the same time, the body of literature is so wide and rich and wonderful and bewildering, sometimes it feels like an endless maze, and this can be exhilarating, and it can be kind of terrifying. This is what I was trying to write about with Judith and the bookshop.

When Veronica finds a body on Mount Wellington it’s autumn, cold, and the young woman appears to have died from hypothermia. You go into details that are gruesome yet compelling. Any comments on writing this scene?

Again, I was thinking about that idea of people being pushed aside. In the classical murder mystery you could argue that the victim dies simply to make the story happen for someone else. I am determined that my readers meet the victims before they die, so that when a body is found it’s immediately clear that this is a person who was once alive. It’s a big theme for me: death is something that is going to happen to us all.

I also think it’s important to look closely at a body, not turn away. Although my milieu is always domestic, I don’t think of my books as cosy. I don’t want my bodies to be just a pair of feet sticking out from under a rose bush. I want us to feel the profound sadness of every death.

While Roland remains elusive his best friend, Paul, becomes increasingly important in the plot. What can you tell us about Paul?

For me Paul is the soul of the book – vulnerable and very imperfect. He has black liquid eyes and he is sensitive to the needs of others. But he is wounded. His mother can’t stand the fact that he’s gay even though she has learned to pretend to tolerate it. He and Veronica have a deep affinity.

Veronica’s mission leads to her being roughed up a couple of times. I liked the realistic way in which you described how awful her injuries felt at the time and afterwards. She didn’t bounce back like a cartoonish PI. Any thoughts about this?

Oh good, I’m glad you liked that. Veronica is a real person to me. I am an un-athletic woman of a similar age and I wanted that to be real. It also shows her strength and determination.

It’s like Paul says about the bottle of wine: “Bring it”. It’s what we do isn’t it, when something important is at stake? We take the damage with us and carry on.

You convey appreciation of the colonial heritage of Hobart (e.g. old buildings being recycled). Some characters feel nostalgia for ‘the old Hobart families’. And, when we meet Veronica — living alone in a big vintage home that’s overdue for repairs — she seems to be an emblem of the old ways being left behind. How do you feel about money-driven urban trends in Hobart: applications to build towers in the CBD, tourist attractions on Mount Wellington, and so on?

I am deeply, deeply attached to Hobart, sixth generation Tasmanian. Tasmania is vibrant and glorious and nurturing and remote and wild.

And fragile.

I do feel a sense of ownership, which I know is unjustified and comes from a position of privilege. (Yes, that notion of ‘old Hobart families’ is an outdated relic from the past and Veronica’s house is crumbling.) I was privileged to grow up there and of course many other people love it and we don’t always agree on what is right for our beautiful place.

BUT I think if Tasmania is to prosper we must recognise what it is that we have that is unique and priceless. Other people come here seeking something. If we turn it into just another place with a cable car and skyscrapers, and if we allow uncontrolled numbers of visitors to damage our wild places, we are in danger of losing our identity and marring our special complex beauty. Even in terms of just the tourist industry I think that would be a huge and sad mistake. But more than that, we would lose our soul.

Thanks so much for your thoughtful responses, Joanna.