The little bird in my latest novel, A Little Bird, isn’t an actual bird, but the anonymous author of a small-town newspaper gossip column. Still, creating my writing ‘bird’ got me thinking about birds and their connection to writing. Metaphorically speaking, the creative habits of writers and birds aren’t so far apart: our storytelling is a form of singing, our flights of imagination a simulation of the real thing. The great Margaret Atwood famously compared fiction writers to magpies—always stealing (or collecting, to be less harsh) shiny objects to create their nests.

Bower birds, too, have some intriguing nest-building habits that echo the creative habits of fiction writers. In contrast to magpies, the collecting of bowerbirds (part of a mating ritual) isn’t for the nest itself, but for decorating the walkway—rather like a deck—that leads up to the nest.

Unlike magpies, who are all drawn to similarly shiny objects, each sub-species of bowerbird collects something different. For instance, some collect bones, which makes for a rather gruesome passage, while some collect only objects of a specific colour—a vivid shade of blue, say, or a lustrous red.

Just like these different bower birds, each fiction writer has their own favoured objects—the stories, the bits and pieces of geography or science, insight into relationships, emotions, history, mechanics, philosophy, politics, sometimes words themselves, that appeal, that make their interior world sparkle. These are the collectibles we transform into fiction and offer up to our readers. And, so we build our fictional nests—some vast and intricate palaces, others more modest, but no less beautiful for that – decorated lovingly with the fascinating titbits, the shiny bits, and pieces, that make our worlds tick, hoping that we can make our readers’ worlds sparkle, too—even if it’s just for a while.

Family, and family connections, often broken or in some way disordered, seem always to be at the heart of my own narrative passageway. The past – sometimes just as gruesome as those bones – features too. But, as for many – most? – crime writers, place is the most treasured collectible – forming the scaffolding that allows for the creation of both plot and character.

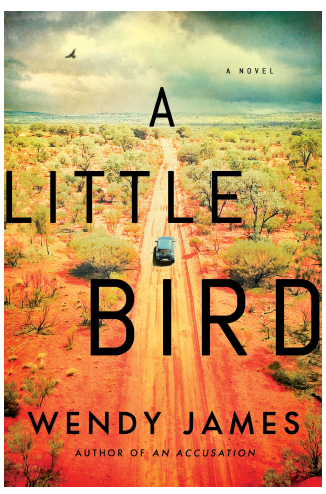

Place is crucial in A Little Bird. It was a Covid book, begun during lockdown, and written during an enforced separation from most of my family – a time when our ideas of what constitutes community were stretched and tested. Set in the invented drought-ridden outback town of Arthurville – a town that resembles the central-western town I grew up in – there’s some nostalgia, but hopefully no sentimentality. Arthurville, once bustling and prosperous, is, like so many small communities, in decline.

Opportunity has dried up along with the land, and everyone is suffering: drugs, crime, unemployment, atomisation. In sending my main character, Jo, back to the childhood home and family she’d once been so desperate to escape, I was given the opportunity, if only metaphorically, to heal some wounds, create new opportunities and possibilities – and in solving the mystery of a long-ago tragedy, put the past to rest.

More info here.