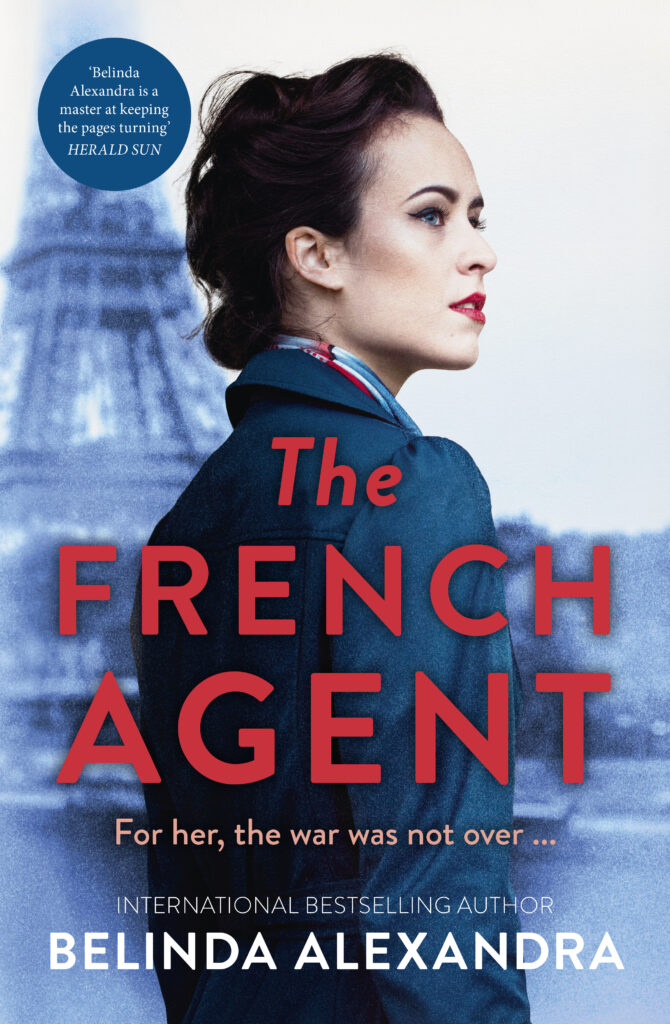

Sydney author, Belinda Alexandra, spoke to Maggie Baron about her latest novel (the 10th), The French Agent (Harper Collins Publishing), and why exploring the issues to do with war – particularly World War 11 – remain so important.

Hi Belinda, firstly congratulations on your successful writing career and for bringing The French Agent to readers. The book covers two storylines based in post-World War II Australia and France.

Sabine is a war crimes investigator with the French Secret Service who is searching for a double agent and traitor—the Black Fox. We also follow Diana White, a landscape designer based in Sydney, who has been waiting six years, for the return of her husband from the war. But Casper is a changed man, now darker, keeping secrets. As the story unfolds their paths are on a collision course, with potentially fatal results.

Without giving anything away, let’s explore this book in more detail.

What made you chose this story? Do you have connections to Europe and World War 11?

My mother’s family were White Russians, and she was born in China. Her family’s life was turned upside down by wars and revolutions. She had relatives who were executed under Stalin and lost a beloved aunt to an air raid. War is a devastating event, so I was interested in writing about what happens to people when the war is over – and they have trauma to deal with.

As a bestselling historical fiction writer, it’s no surprise to see this crime thriller is set in war times. But you’ve placed the story firmly in the aftermath of World War II. What attracted you to positioning the book in 1946, rather than the formal war years?

A lot has been written about the German occupation of France and the French Resistance. But what I was interested in what happened after the Germans left, and the French people who had collaborated and those who resisted had to face each other. I also wanted to bring the story to Australia. Our country was relatively untouched by war, compared to Europe, but one million servicemen and women had participated in the armed services in some way and their lives were never the same. They returned home, and their spouses and families were expected to help them get through what we now recognise as PTSD – something they were not qualified for and made them feel helpless and isolated in their inability to help.

The story covers multiple characters, in various settings—both geographic and from varying points of view. How did you tackle the technical challenges presented by this approach?

During lockdown, I did a masterclass in screenwriting. It gave me an appreciation of how to cut various scenes together for dramatic effect. Of course, a novel is different to a film, but I was able to adapt some of those screenwriting techniques to The French Agent. I can’t say it was an easy task, and I had to work closely with my editor to make sure it all flowed in a way that made sense, but I think it suited the story perfectly.

You touch on numerous war crimes and the mistreatment of people. What are you thinking about when you write these aspects, to ensure you’re being historically accurate, yet sensitive to those who suffered and died?

I know it’s a paradox, but I write about war because I’m anti-violence. War is the worst expression of human existence. I’m not very comfortable with historical fiction that romanticises (even glamorises) war – I know from my mother’s stories that war is horrific. The best I can do is to be accurate about the cruelty, greed, and senselessness – but also the heroism, grace, and humanity – that comes out of such an extreme event. I try to be truthful but not gratuitous. To make people think seriously about violence and hate, and the consequences of it, is the best way I know to honour the dead.

What encouraged you to create the character of an Australian mid-century landscape designer—Diana?

I love gardens and one of my great personal influences is Edna Walling, who was a pioneering landscape designer and conservationist active from the 1920s to her death in the 1970s. For me, a garden represents hope, beauty, and faith in the future. Diana’s garden is the symbol for that in the book.

How did you ensure the settings of mid-century Sydney were accurate?

I read newspapers and magazines of the time. It gave me insight into what people were thinking and what their main preoccupations were. Edna Walling, whom I mention above, wrote a column for Home Beautiful Magazine, which helped me get the garden styles and home décor accurate. Then I would look up books on Sydney and its architecture and infrastructure to get an overview of what the city was like.

This is your 10th fiction novel. What motivates you to write more books?

The stories in my head are like trains – one pulls out of the station and another one comes in. My characters are like guests in a hotel – one lot leave and another arrive. I rarely have an empty space in my head. There is always another story bursting to be told. I’ve been like that since I was a child.

Can you tell your readers what you’re currently working on?

Yes, another mystery set in France in 1946. A young woman is trying to defend her father against the charge of collaborating with the Nazis by selling an important painting to Hitler’s art dealer (and having murdered the original owner to get his hands on it). My character must find the painting’s whereabouts before the villain of the book does.

More info here.