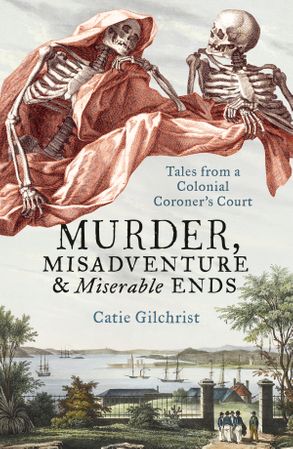

Author: Dr Catie Gilchrist

Publisher/Year: Harper Collins/2019

Publisher overview

Murder, manslaughter, suicide, mishap – the very public business of determining death in colonial Sydney.

Murder in colonial Sydney was a surprisingly rare occurrence, so when it did happen it caused a great sensation. People flocked to the scene of the crime, to the coroner’s court and to the criminal courts to catch a glimpse of the accused.

Most of us today rarely see a dead body. In nineteenth century Sydney, when health was precarious and workplaces and the busy city streets were often dangerous, witnessing a death was rather common. And any death that was sudden or suspicious would be investigated by the coroner.

Henry Shiell was the Sydney City Coroner from 1866 to 1889. In the course of his unusually long career he delved into the lives, loves, crimes, homes and workplaces of colonial Sydneysiders. He learnt of envies, infidelities, passions, and loyalties, and just how short, sad and violent some lives were. But his court was also, at times, instrumental in calling for new laws and regulations to make life safer.

Catie Gilchrist explores the nineteenth century city as a precarious place of bustling streets and rowdy hotels, harbourside wharves and dangerous industries. With few safety regulations, the colourful city was also a place of frequent inquests, silent morgues and solemn graveyards. This is the story of life and death in colonial Sydney.

Reviewer: Narrelle M Harris

Social history, especially as it pertains to murder and crime, will always be a lure to get me into a book. Catie Gilchrist’s account of Henry Shiell’s 33 year tenure as colonial Sydney’s City Coroner through a selection of the cases over which he presided has been on my wish list for a while.

The cases that passed through Shiell’s court between 1866 and 1899 are presented in distinct categories: murder, manslaughter, suicide, accidental deaths occurring through the hazards of work, transport and daily life, and the deaths resulting from unwanted pregnancies, either through abortion or infanticide. It’s a sad and sometimes sensational record of life and death in a colonial city and the usual spread of human suffering, passion, cruelty and pity.

Gilchrist doesn’t simply provide a litany of cases and their outcomes – her research into various cases comes with commentary of how Sydney society responded to notorious and sometimes heartbreaking cases. She also records the instances of when inquests resulted in suggestions for changes in laws and attitudes – whether such calls for change were ignored, embraced or took several years for authorities to act.

Gilchrist adds her own observations on how poverty and societal attitudes towards women and men affected various kinds of deaths, remarking with asperity particularly on damaging and contradictory attitudes to women and the poor (and poor women especially) that created situations in which so much tragic death occurred.

The author’s occasional tendency to withhold the names of key perpetrators for effect was occasionally frustrating. The reader needs to stay alert too, as cases mentioned one or more chapters ago might come up again to demonstrate the timeline. (I took a four week break between starting and finishing this book, which meant I lost track a little!)

Those quibbles notwithstanding, I read Murder, Misadventures and Miserable Ends: Tales from a Colonial Coroner’s Court with morbid fascination and finished it with a greater understanding of the conditions in Victorian-era Sydney. My copy is now festooned with sticky notes against cases and relevant laws that I may refer to for further research in my own writing.