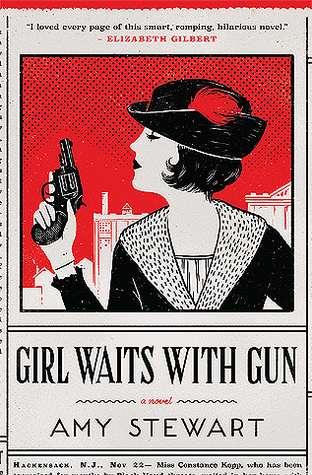

Publisher: Scribe

2015 & 2016

Reviewer: Robyn Walton

Synopsis

In Girl Waits with Gun Constance Kopp doesn’t quite fit the mold. She towers over most men, has no interest in marriage or domestic affairs, and has been isolated from the world since a family secret sent her and her sisters into hiding fifteen years ago. One day a belligerent and powerful silk factory owner runs down their buggy, and a dispute over damages turns into a war of bricks, bullets, and threats as he unleashes his gang on their family farm. When the sheriff enlists her help in convicting the men, Constance is forced to confront her past and defend her family — and she does it in a way that few women of 1914 would have dare.

Lady Cop Makes Trouble sets Constance loose on the streets of New York City and New Jersey–tracking down victims, trailing leads, and making friends with girl reporters and lawyers at a hotel for women. Cheering her on, and goading her, are her sisters Norma and Fleurette–that is, when they aren’t training pigeons for the war effort or fanning dreams of a life on the stage.

Reviewed by Robyn Walton

The small industrial city of Paterson, New Jersey has a surprising number of connections with authors who have either lived there or written about it: William Carlos Williams, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Nelson Algren, John Updike, Junot Díaz. It’s the setting for the triple murder in Nobel laureate Bob Dylan’s ‘Hurricane’, his protest song about boxer Rubin Carter. Film-maker Jim Jarmusch, who has had a long-time interest in Paterson’s history of silk-weaving mills, workers’ strikes and immigrant presence, this year released his film Paterson, featuring a poetry-writing bus driver. And 2016 has also seen the publication of two novels by American author Amy Stewart set in Paterson and other New Jersey locations in 1914-15.

Stewart’s enticingly titled Girl Waits with Gun and Lady Cop Makes Trouble are the openers in a projected series based on the experiences of three real-life women, the Kopp sisters. The eldest sister was one of the first American women employed in law enforcement duties that extended beyond serving as a matron in a jail or asylum. And later all three sisters worked in their own private detective agency.

These novels follow a successful run of six non-fiction titles in which Stewart brought her upbeat narrative style to the world of natural history, progressing through topics as unpromising as earthworms and toxic plants to her New York Times best-seller The Drunken Botanist (2013) about the plants that form the basis of alcoholic drinks. Throughout, Stewart maintained the persona of an intellectually inquisitive amateur equally prepared to roll up her sleeves and defer to respect-worthy authority. Now she is bringing a comparable approach to her fact-and-fiction hybrid novels. With a light touch and droll humour, she crafts sustained plots out of material that in less skilful hands might remain as dead as a post-exploitation silkworm.

In Chekovian fashion Stewart’s sisters occupy a provincial farmhouse, having left Brooklyn a few years earlier. They are educated, mildly discontented and running out of money. There is also at least one significant secret in their backstory. As the eldest sister, narrator Constance Kopp wants to generate enough income for the trio to remain living independently of their irritating older brother. Middle sister Norma attends to the farm work, her penchant for reading news reports aloud and clipping amusing headlines serving Stewart’s need to indicate the social context of the sisters’ domesticity. Home-schooled teenager Fleurette is flighty, creative and attractive.

The agent of disruption in Stewart’s first novel is a silk-dyeing factory heir, Henry Kaufman. His careering motor car slams into the sisters’ horse-drawn buggy at a Paterson intersection. Constance’s requests for the cost of repairs provoke intimidating messages from Kaufman’s henchmen. Fortunately for the sisters, the conscientious and progressive Sheriff Robert Heath (another character adapted from real life) takes an interest in their welfare, and soon visiting law enforcement officers are substituting for Chekhov’s visiting soldiers. No courtships ensue but there are muted interchanges. “Sheriff Heath … leaned down to offer his hand to me. I didn’t need it, but I took it.”

Heath is aware of the Kaufman thugs’ complicity in liquor smuggling, illicit gambling and extortion rackets, à la the Black Hand gangs of some Italian-American communities. And the novel’s subplot focuses on the repercussions of the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike for mistreated women workers and their young children.

Following attacks on the Kopp farmhouse, Heath equips the besieged older sisters with revolvers and teaches them to fire them. Then, after a threat to abduct Fleurette and sell her into white slavery, he sets a trap. Constance is to meet her tormentor to hand over the blackmail money demanded. On a Paterson corner, she waits, her revolver in her handbag. ‘Girl Waits with Gun’: in fact, Constance was aged 35 and was unusually tall and strong, yet this was how one of the contemporary newspapers represented her, as Stewart relates in her source notes. Once Kaufman is finally convicted, Sheriff Heath proposes Constance take the job of Deputy Sheriff.

Stewart’s sequel novel, Lady Cop Makes Trouble, is shorter and closer to a conventional crime yarn. Constance is up against the self-styled Rev. Dr. Baron Herman Albert von Matthesius, arrested for fleecing nerve patients through his sanatorium. She is motivated to pursue the old reprobate after he escapes from jail during her watch as matron and unofficial guard. Investigations take Constance to a variety of respectable and low-life locations in New Jersey; and in New York City, 35km away, she succeeds in arresting a von Matthesius relative for harbouring the fugitive. Between excursions Constance oversees colourful local culprits and encourages Fleurette’s first stage appearance as a singer, while Norma busies herself training messenger pigeons. Poet William Carlos Williams fleetingly makes it into this second novel in his role of medical practitioner when Constance travels to Rutherford, his home town.

Australians who’ve read or watched on television the crime solving capabilities of Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher and her assistant Dot in late 1920s Victoria are likely to appreciate Stewart’s characters and her delving into pockets of social history. The tight time frame of the Stewart novels means readers glimpse both welcome and concerning trends in societal change much as the characters do. The present post-industrial terrain of Paterson is not something we can expect Stewart’s characters to predict; however, we do see them dealing with the impacts on the lower social strata of mill owners’ moves into mechanization.

This article first appeared in The Weekend Australian 10-11 December.