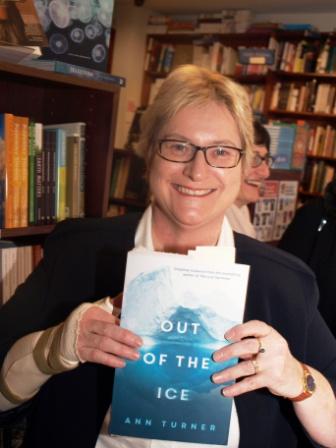

Q&A. Ann Turner, author of Out of the Ice (Simon & Schuster) tells Robyn Walton, a Sisters in Crime Australia national co-convenor, what makes her Antarctic thriller so chilling.

Hi Ann. There’s a lot going on in your second novel, Out of the Ice, and a number of wide-ranging, serious issues are raised. I can’t hope to cover everything, so I’m going to concentrate on two aspects, locations and female characters. At the end you may like to add some remarks on other aspects that were important to you as you wrote.

Locations first. You take your protagonist, scientist Laura Alvarado, to places that are both visually stunning and disturbing. Film-maker George Miller tells the story of making Happy Feet, his animated movie featuring dancing penguins, after a veteran photographer recommended Antarctica as a spectacular setting. You were a successful screenwriter and director before you turned to novel-writing. What got you interested in Antarctica and can you imagine collaborating in making a film set there?

This is a great question, as the idea for writing about Antarctica actually started for me almost three decades ago as a film. I saw a beautiful book of Antarctic photography, and there was a magnificent photo of penguins dancing on the ice, and a visually stunning ice cave. From that moment I was hooked, and started writing a screenplay for an action-thriller set in Antarctica. At that time, I was a writer-director, and after a few drafts I felt it was too high-budget for me to direct, and so I put it aside and developed other films. But the place haunted me, and so when Simon and Schuster offered me a two-book deal when they picked up my first novel, The Lost Swimmer, I jumped at the opportunity to write about Antarctica again. The screenplay was set in the near-future back then, and I’d spoken to futurologists in my research. Fascinatingly, almost all the innovations they predicted had come true. I decided to write a completely different story, set in the present, and on a wild Antarctic island. But I can definitely see this narrative as a film too – albeit a very expensive one! I think the locations, action, and characters would all translate well to the big screen. Perhaps one day… And it’s still too big for me to direct, but that’s no longer a concern as I absolutely love writing and feel that’s where my future lies.

Your novel’s Antarctic and sub-Antarctic locations seem to be modelled on real settlements. For instance, your abandoned Norwegian whaling station resembles Grytviken, which is accessible to tourists. How valuable was first-hand research?

I read many, many books, researched thoroughly on internet sites, and talked to experts. I wrestled with whether to go on a cruise to Grytviken, but decided that my whaling station was more pristine than I’d find Grytviken, and I had a very good idea, from the books I’d read, of the architecture of all the whaling stations on South Georgia Island (in the hey-day of whaling, there were another five whaling stations as well as Grytviken on the island). My whaling settlement of Fredelighavn resembled a combination of these whaling stations, with some fictitious elements added. I decided in the end it was more important for my research to visit a whaling museum in Sandefjord, Norway, which was the whaling capital from where the whalers who went down to South Georgia, and Antarctic waters, set off. Commander Chr. Christensen’s museum gives a very clear insight into the whole Norwegian whaling endeavour, and there were photographic books, from their archive, that you can get nowhere else. These pictures of Grytviken, taken when it was operating, were invaluable to my research. For example, early on I read that there were no women on the whaling stations – but here in the books were photos of wives and daughters of the Station Manager and doctor, for example, and they were sitting around smoking pipes!

The alternative to being outdoors in the unpredictable Antarctic environment is being inside. You take your readers into underground science labs, tunnels and other dark enclosures that may or may not be dangerous. To what extent did you mean to scare and horrify us? And were you influenced by science fiction or other genres?

I did hope to unsettle the reader, and I always love underground locations for their links to our collective unconscious. And what lurks beneath the surface lends itself very much to a horror/thriller twist on things. I was influenced by science fiction too. I grew up in Adelaide watching Aweful Movies with Deadly Earnest, where they showed a lot of horror and sci-fi. One of the films that particularly drew me in (among many) was the original 1951 version of The Thing, a science fiction horror film set in the freezing Arctic. There were very hollow sound, grainy black and white images, and a truly unnerving feel. Howard Hawks was an uncredited director on it. The fear portrayed from the unnatural elements wreaking havoc in the ice left an indelible impression on me, and I drew from that as I was writing Out of the Ice. While I see my novel as a mystery-thriller, there are definitely horror influences. I also have my central character finding a list of films the whalers watched at Fredelighavn (and the whaling stations really did have cinemas). My whalers enjoyed Val Lewton films such as I Walked with A Zombie, Curse of the Cat People (a favourite of mine and an influence on my own first feature film Celia), and The Body Snatcher. I love the idea of people in the Antarctic watching scary movies – and I believe it’s somewhat of a tradition on Antarctic bases even to this day.

From Antarctica your protagonist, Laura, hurries to North America, to Nantucket, another place with a whaling history. Here Laura’s motherly host provides comfort foods and a soft bed. As author did you feel relief from past and current traumas was in order?

The gentle, nurturing characters of Nancy and Helen on Nantucket were inspired by hosts at American inns where I’ve stayed, who baked delicious treats and had beautiful, warm lodgings. As Nancy and Helen came alive to me as I wrote, I did think they created a peaceful haven for Laura, albeit briefly. The island of Nantucket has such a violent, bloody whaling past, and yet it is also quite magical. In the book I try to draw out those ethical dilemmas of people doing things they don’t think are wrong, and which many of us think are very, very wrong. Nancy and Helen hold conflicting views about whaling – and the trauma for Laura, and Helen, about whaling is never far from the surface, even in the tranquil environs of Nantucket. But I really wrote this section being led by the characters; I didn’t stop and think as an author that I felt relief was needed. In any event, Laura is still completely haunted by what she thought she saw in the ice cave.

The story moves on to Europe, as it did in your first novel, The Lost Swimmer. Do all roads lead to Venice? Had you set your heart on writing your version of a classic movie scenario set in Venice?

Venice is in both novels, but this is a very different side of Venice – flooded by the tide at acqua alta, dark, misty and threatening. The action that takes place there was one of my starting points for the migration theme, and based on real events that occurred in Venice. It was important to use it as a location, because I wanted that element of veracity. And the movie Don’t Look Now, set in Venice, was an inspiration for the mood I wanted to create in the novel. And I liked the way Venice is a long way from Antarctica, echoing the vast distances whales travel in their migration, and the vast expanses of ocean traversed by the whalers from their homes in the Vestfold region of Norway to Antarctic waters. So certain roads lead to Venice, and for a reason. I hadn’t set my heart on writing a version of a classic movie scenario there – but it is a homage to a favourite movie!

Now I hope you’ll tell us a little more about your thoughts and feelings as you developed your female characters.

I was really interested in telling a story in Out of the Ice that depicted female friendship: how deep the bonds can be, and how much support women give each other. I also wanted to write about strong women, women who lead the action. With Laura, I chose to have a central character with a troubled past. It is her, in the end, who needs to find her way at a personal level out of the ice. Along the way she is helped by Kate, who is someone happier in the presence of penguins than humans, but still a wonderful, level-headed, at times constructively cynical (in the best possible way) friend to have. And their Station Leader Georgia who they adore, who is a tough, highly intelligent detective with the Victoria Police taking a stint at an Australian base in the Antarctic. The loyalty the women show to each other is something I felt was important to depict. I was also interested to have Australian women leading an investigation for the fictitious international Antarctic Council. As a film student I grew up with Australian movies that often depicted women as victims, and Australians generally as losers. I loved being able to make my women strong, forceful – and (mostly) winners. And of course Nancy and Helen on Nantucket are two more women in the novel who share the enduring bond of friendship.

Laura’s ornithologist colleague Kate is passionate about wildlife and anxious on its behalf. Among the thousands of creatures monitored by Australian scientists we encounter Lev the humpback and Isabel and Charles the penguin couple. Any comments?

Lev the humpback is a very important character in the story. Humpback whales can be identified by the black and white patterns on their tail flukes, and Laura has encountered Lev on several occasions: first as a young calf, and later, among other times, as a full-grown whale she swims with. Laura finds that Lev cares about her with the way he moves his giant body as he comes close, so as not to hurt her. This is something that researchers of whales have encountered with humpbacks. The male humpbacks also sing to attract mates, and each pod’s notes change slightly, every day, and spread across the ocean from one humpback community to another, in a giant, progressive round of song. Whales’ communication skills are thought to be more advanced than humans. Which makes slaughtering them – as some countries still continue to do – so completely abhorrent.

Kate’s passion for penguins and her anxiety for the wildlife mirrors many of us who fear for wilderness areas and the damage humans can inflict. Kate lives for her penguins, and it’s thought Adélie penguins mate for life, hence her interest in satellite-tracking couples such as Isabel and Charles. Kate names her penguins to identify them – but I think it’s more than that with her too. There’s a deep affection, and personal connection.

Laura’s mother is a professor of Spanish. Indeed, almost every adult in Laura’s world is a brainy high achiever. Did you ever worry about daunting your readers?

I wanted to show high-achieving women, because I think there are a great many extraordinarily talented women in this world. The men in the novel are also high achievers as they are hard-working scientists and engineers. I certainly hope this doesn’t daunt readers – it’s who these people are, carrying out their research. I do think, though, that Laura has struggled with having two very high-achieving parents and feels she hasn’t quite lived up to their standard. So she’s a bit daunted.

Station Leader Georgia Spiros, a senior detective in the Victoria Police, roars up on a skidoo, black hair flying, looking ‘like a fiery superhero’. You like to depict women who are strong and physically energetic?

Absolutely, and I think to be at a base in the Antarctic you need to have a high level of physical fitness. And Georgia is someone who Laura and Kate really look up to. As a detective, she’s strong and smart. I like writing about those sorts of women. I’ve always loved reading about them too – characters like Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski. Sara Paretsky is an author I admire greatly, and certainly inspires me as a writer.

The (fictitious) village attached to your novel’s (fictitious) whaling station was largely developed and run by a woman. Are we under-informed about women’s contributions in Antarctica, commerce, science …?

History is told by the teller, and women have often been written out of it. To that end, I think throughout the ages we have not heard fully of women’s roles, or indeed the place of women in events has often been neglected. Even the type of history that has been told over the years has tended to neglect areas classed as less masculine, such as emotions and memory. It’s fantastic that we now have great women historians who are writing history from a feminist perspective – history that is being told for the first time. For instance, books on memory and war, migration and loss. In my own small way, I wanted to nod towards the absence of women in so many histories, hence the inclusion of Ingerline Halvorsen, who was the driving force behind the whaling station of Fredelighavn through the really difficult years after her husband died. I think women are often allowed into positions of leadership in the very toughest times – and we certainly see that in politics.

Finally, Ann, would you like to draw readers’ attention to any other aspects of the novel?

Thanks so much for these fascinating questions, Robyn, and I hope readers enjoy travelling down to Fredelighavn among the rainbow-coloured buildings, the haunted whaling station, and the extraordinary wildlife. And journey with Laura as she tries to solve the mystery of the secrets that are hidden beneath the ice.

Ann Turner and L A Larkin will talk to Hazel Edwards about their new Antarctic thrillers on Friday October 7, 8pm at the Rising Sun Hotel in South Melbourne. Bookings: http://antarticnoir.eventbrite.com