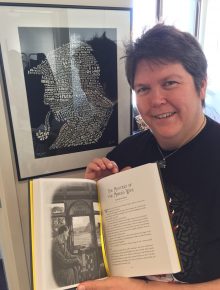

Narrelle M Harris

I was a late bloomer when it comes to Sherlock Holmes. The first Holmes I knew was through television and film, and while the general idea of the character and his cases were intriguing, portrayals of Holmes as patronising and Watson as incredibly stupid didn’t light a spark in me.

Then came the Granada TV series (1984-1994) starring Jeremy Brett and David Burke, so sparkling and smart that it sent me back to Conan Doyle’s original stories.

I’ve been a dedicated Holmes-and-Watson fan ever since.

My love of the characters extended to the first few seasons of the BBC reinvention of the characters for the 21st century. That series, and fan response to it, led me to think more about interpretations of their relationship. Epic best friends or potential lovers? It’s always struck me that they’re both valid interpretations in the modern era. Even the US series, Elementary, portrays Holmes as a sexual being, and even a romantic one.

I’m still not wedded to any particular interpretation of the characters. Sherlock Holmes can be asexual; Watson bi; both straight; both gay. I’ve read variations on them in terms of gender and sexuality, including trans interpretations.

I’ve written my own too: The Adventure of the Colonial Boy is an adventure sent in Australia in 1893, in which they solve a case, encounter a red leech and admit their love for each other, despite the social dangers. I’ve written them as modern men falling in love too, for a story in A Murmuring of Bees.

Yet a romantic relationship isn’t the only possibility I see, and I continue to write more traditional epic-besties interpretations, which have been published in the MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Parts V and VI, in the upcoming Baker Street Irregulars 2 anthology of alternative universe stories, in which I’ve made them a couple of Melbourne hipster baristas.

Someone once asked me, given my broad approach to reading the famous friendship, what I thought the core of a Holmes story had to be to still be a Holmes story. Whether or not they are lovers seems neither here nor there, when you consider that in their history they have variously been African American (New Paradigm’s Watson & Holmes comic), women (The Adventures of Shirley Holmes), robots (Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century), a puppet (2014 Japanese Sherlock Holmes), a dog (Sherlock Hound) and mice (The Great Mouse Detective).

For me, the core of the stories of Holmes and Watson are adventures and friendship. And whether they are genderswapped, anthropomorphised rodents, clockwork or in love with each other, if they have friendship and cases, that’s Holmes enough for me.

All of this leads me to Sherlock Holmes: The Australian Casebook.

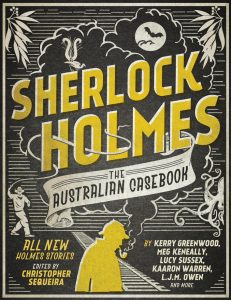

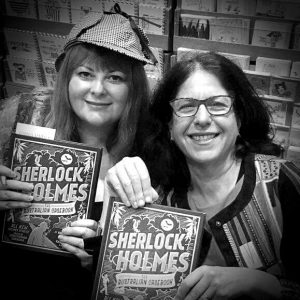

Edited by Christopher Sequeira, and published this month by Echo Publishing, The Australian Casebook sees Holmes & Watson solving mysteries around the colonies in 1890.

It’s a fabulous, illustrated production with 16 tales of mystery and derring-do, by 17 Australian writers, including fellow Sisters in Crime members, Kerry Greenwood & Lindy Cameron, LJM Owen, and Lucy Sussex.

My story, The Mystery of the Miner’s Wife, is set in Ballarat in 1890. But what draws writers to the Great Game of writing Sherlock Holmes stories?

I asked my fellow contributors to Sherlock Holmes: The Australian Casebook for their thoughts.

For some, the appeal is the nature of the mysteries. ‘Most are very much “think outside the box” situations,’ says Raymond Gates, who wrote The Sung Man. ‘We’re all trying to figure out this great mystery called life. SH & DW give us the sense that any mystery can be unravelled. So maybe our own can as well.’

‘There are no cheats in Doyle’s stories, no short-cuts or cop-outs. The puzzle is solved brilliantly every time,’ agreed Kaaron Warren, who contributed Shadows of the Dead, which includes Australia’s first female doctor, Constance Stone, as a character.

For others, the setting itself is half the charm. Jan Scherpenhuizen, author of The Adventure of the Demonic Abduction – and illustrator of my own story, The Mystery of the Miner’s Wife – loves ‘the romance of Victorian/Edwardian times and the language’. However, it all comes back to the characters in the end: ‘The characters in Doyle’s stories are so well-drawn and distinctive that, combined with clever plotting, they’ve become truly timeless classics.’

Bill Barnes, who wrote the book’s introduction, encapsulates another and more social reason for our shared love of Sherlock Holmes. ‘I love the friendships I have gained from a shared interest in their adventures. I love being able to travel the world and hook up with local Sherlockians, people I’ve never met before but with whom I become instant friends.’

Almost overwhelmingly, though, it’s the partnership of Holmes and Watson that brings all the writers to the yard.

‘The characters balance one another out,’ says Robert Veld, who drew on his own convict-related family history for inspiration for The Murder at Mrs Macquarie’s Chair.

‘Under normal circumstances, these two vastly different individuals would not cross paths. However, through a unique set of circumstances, these two come together and find that they actually need and depend on one another. When you read a Sherlock Holmes story for the first time, you go in search of a great mystery story. When you go back to that same story throughout your life, long after you are well aware of the plot, you are going back for something else: Holmes & Watson.

Veld expanded on the idea. ‘Doyle experimented with a couple of Holmes-narrated stories. These are very poor by comparison to the others. Watson wasn’t there and it just wasn’t the same. People are drawn to the genius and cleverness of Sherlock Holmes but in the process they also discover Watson. They find that Sherlock Holmes would actually be downright dull without his best mate to narrate his adventures and keep him grounded and on track. Holmes frequently admits as much! There are few greater partnerships in all of literature.’

Fellow Sister, Lucy Sussex, says, ‘I thought it would be fun for Holmes to meet a female feminist detective. And as it happened they got on famously.’ Her story, The Story of the Remarkable Woman, is set on a steamer travelling between Australia and New Zealand.

The Adventure of the Flash of Silver writer, Doug Elliott, is another with a fondness for the ‘enduring bromance’ of Holmes and Watson. ‘The mystery isn’t just an intellectual puzzle; it’s crafted around a very human core. I also give a lot of credit to Conan Doyle’s writing style. It’s very 20th century.’

Jason Franks contributed The Problem of the Biggest Man in Australia. ‘Bringing Holmes to a nation of convicts is a way of putting the man in his element,’ he said. ‘The fact that we experience everything through Watson’s narration provides suspense and also helps us to weather Holmes’ condescension, because Watson is a highly intelligent man in his own right. Without Holmes’ flawed persona and Watson as a sympathetic foil, I don’t think these stories would have lasted the way they have.’

Meg Keneally, who wrote The Play’s the Thing, agrees. ‘Sherlock has always been almost like an alien, preternaturally intelligent and perceptive; someone to admire, but not someone who’s easy to relate to. Watson makes Holmes accessible by revealing his friend’s humanity as well as his own. Holmes needs Watson to translate the world for him, and translate him for the world. And I’ve always had a weakness for stylish baddies. Enter Moriarty.’

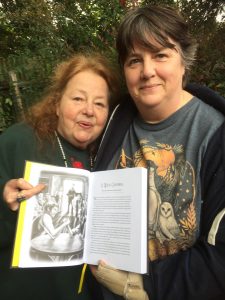

Sisters in Crime President, Lindy Cameron, joined forces with founding member Kerry Greenwood, to co-author A Wild Colonial. Set in South Australia, theirs is a tale of shearers and bushrangers, murder and mistaken identities. ‘The best part for me,’ says Cameron, ‘was collaborating with the creator of Phryne Fisher! Kerry and I are great friends, but I couldn’t ask for anything better than concocting a Sherlock Holmes mystery with Kerry. We had great fun researching South Australia in the late 1880’s in order to lay a good foundation for setting our story in a very real 1890.’

Sisters in Crime President, Lindy Cameron, joined forces with founding member Kerry Greenwood, to co-author A Wild Colonial. Set in South Australia, theirs is a tale of shearers and bushrangers, murder and mistaken identities. ‘The best part for me,’ says Cameron, ‘was collaborating with the creator of Phryne Fisher! Kerry and I are great friends, but I couldn’t ask for anything better than concocting a Sherlock Holmes mystery with Kerry. We had great fun researching South Australia in the late 1880’s in order to lay a good foundation for setting our story in a very real 1890.’

TSP Sweeney’s The Case of the Vanishing Fratery is his first Holmesian story, though he’s been a reader since his father first gave him ‘yellowed and dog-eared old books’. Writing a story set in Australia provided Sweeney an opportunity to explore the history of his home as well as of placing these familiar characters into a destination on the opposite side of the world.

‘Australia represents a lot of unique storytelling opportunities, both in general, but also in this particular time period,’ says Sweeney, who also responds to that famous friendship. ‘There’s something about the odd-couple pairing that strikes a chord in so many people. All the representations that I’ve seen of their friendship emphasise the mismatch in personality and approach that Holmes and Watson have. It serves to bring them closer together as better partners and detectives. It also, of course, lays the grounds for the particular challenges their friendship can face, because all good friendships get tested after all!’

Long-time Holmes writer Christopher Sequeira commissioned the anthology as well as contributing The Dirranbandi Station Mystery. ‘It’s set in Dirranbandi, Queensland in tribute to my late mother, who was born there’.

‘I love everything about Holmes and Watson,’ he says. ‘They are the first ‘modern’ science series heroes. In some ways they’re the predecessors of the superhero, driven by justice rather than lower motives. Doyle really created a whole slew of story-telling tropes that have become ingrained in the culture: no mean feat!’

Sisters in Crime member, Dr LJM Owen’s take on why the characters endure is not unlike my own.

‘The potential for the reinvention of Holmes and Watson as endlessly curious, energetic characters is what keeps them alive in the collective Holmesian imagination. [Readers and writers] seem to draw the characters into their subconscious and fall captive to the game of ‘What if?’. What if I were Holmes? Or Watson? What if they encountered a case in such and such a time or place? What would they make of modern forensic technologies?’

Dr Owen’s The Adventure of the Lazarus Child draws on the what-ifs of a real mystery in 1890s Queanbeyan, where a child was pulled, apparently dead, from a trench, only to revive two days later.

‘I was excited to explore how both Holmes and Watson would fare in unknown territory. How would Holmes orient himself in the Australian landscape given the comfort he derives from his familiarity with London’s environs? What would he make of the new modes of death offered by Australian fauna? How would he and Watson fare in the extremes of our climate?’

How indeed? Sherlock Holmes: The Australian Casebook gives you at least 16 answers to all of those questions, and probably to some you never thought to ask.

The book is available from all good book shops. Truly.