Allen and Unwin

2016

Reviewer: Jacquie Byron

Synopsis

Recently divorced and trying to make sense of her new life, Anne takes her daughter Aida on an overnight bushwalk in the moody wilderness of Wilsons Promontory. In a split second, Aida disappears and a frantic Anne scrambles for help. Some of the emergency trackers who search for Aida already doubt Anne’s story.

Nearly two years later and still tormented by remorse and grief, Anne is charged with her daughter’s murder. Witnesses have come forward, offering evidence which points to her guilt. She is stalked by the media and shunned by friends, former colleagues and neighbours.

Review by Jacquie Byron

Baxter heads out camping on the Wilsons Promontory with her six-year-old autistic daughter, Aida. The child goes missing but it takes almost two years before Anne is accused of murdering her and disposing of the body. Undoubtedly this synopsis is too simplistic but hopefully enough to give you context. Ann is the ex-wife of a prominent barrister and the mother of another daughter, the university-aged Hannah. Grieving and guilt-ridden, she undergoes a horrific and destabilising journey, from ex-journalist and member of a privileged Melbourne bayside community to – alternately – a detained person and also a virtual prisoner in her own home, spat on by strangers in the street and abused by online stalkers and anonymous phone callers.

Author, Olga Lorenzo, apparently shares some of Anne’s professional and personal background. Both women served time as newspaper journalists and Lorenzo gives loving credit in her author’s note to the blended family she and her first husband have formed with new partners. Anne Baxter faces similarly blurred familial lines as Robert, her haughty ex-husband, enjoys married life to the seemingly more malleable Sandra. Anne’s impulse to dislike the new wife and discourage any affection Hannah feels towards her is uncomfortably human.

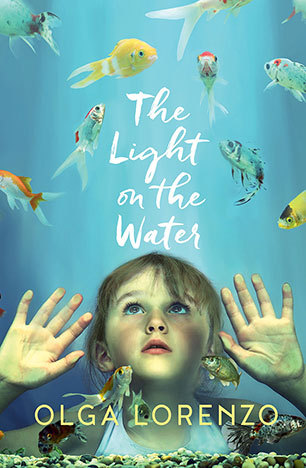

The Light on the Water is one of those books that lingers. On a sensory level, it is highly evocative. Without being showy or overblown, Lorenzo deftly brings to mind the searing heat of Melbourne in drought, the sights and sounds of bayside cliff walks, the incidental characters in an inner-city café. She locates her story very precisely. Conversations are held in Carlton or near the carpark at Half Moon Bay. The ever-present aquarium in Anne’s home is populated by imperilled angelfish and the more robust guppies.

Such attention to sometimes mundane detail gives the book its power. In the middle of a so-called normal life, awash with the usual marital woes, childrearing challenges, domestic rituals and workplace obstacles, a woman who considers herself highly maternal can find herself vilified in newspaper headlines and shunned by the girl at the local store. Her six-year-old daughter can disappear without a trace and people, including family members, can blame her.

To call this a crime novel is misleading. Yes, the main character is accused of a crime but readers anticipating a thriller or whodunit won’t be satisfied. Read on anyway. Like Anne herself, a dedicated bush and coastal path walker, The Light on the Water treads a number of sometimes disturbing, always engrossing paths.

The idea that Anne really did kill Aida never felt likely to me. How can a woman who dusts the items in her missing child’s room “like a caress, the only one she can offer”, have done such a thing? The real sense of fear and suspense comes from the way Lorenzo all too believably depicts the power and destruction that is possible when vicious tongues, hostile legal professionals and an alarmist media join forces.

This book is an excellent portrayal of human flaws, of a woman’s flaws in particular – as a mother, a wife, a daughter, a sister and even a neighbour. At one point Anne reflects on the time someone asked her if she loved one daughter more than the other, the insinuation being that a disabled child was not as loveable. Anne doesn’t shy away from her most private response. She loved both her daughters deeply but Hannah, without the challenges of autism, was merely sometimes easier to love. How many parents have known that feeling over the ages, based simply on the personalities or behaviours of their kids, not needing an illness or disability thrown in?

Lorenzo is skilled in terms of switching timeframes without confusing the reader. A conversation about a tea set can lead us to a time when Hannah was a toddler, her father a distracted babysitter. Flashbacks or reminiscences, whether to the last tragic walk at the Prom, or the way divorce alters social landscapes, are always enlightening, moving the story onwards.

As a writer, Lorenzo (in real life) must be an amazing watcher. She precisely notes the often-subtle changes in people’s behaviour that actually telegraph cataclysmic changes in attitude or affections. Anne’s best friend Linda, still a hardworking newspaperwoman, sounds slightly breathless during a phone call, for instance, meaning Anne immediately knows talk of renewed police interest is cause for alarm. When Aida first goes missing Anne, possibly informed by Lorenzo’s years as a reporter, recognises the emotions of the gawking onlookers. Anne reflects, “… they were trying to live through her, to experience this second-hand, as if rehearsal could prepare them.”

Funnily enough, Lorenzo finishes that paragraph musing over whether this is the reason people sticky-beak at road accidents or even read books. The Light on the Water might back this theory up. How does it feel to literally lose a child, to look away for a moment and find them gone? What it is it like to have a differently abled child? To be married to an over-achieving man? To have a mother you hate and a sister who torments you? Lorenzo explores all these questions sensitively and deeply while maintaining great momentum with her storytelling, enhanced by the occasional bolt of wry humour.