2016

Echo Publishing

Reviewer: Anne Buist

Overview:

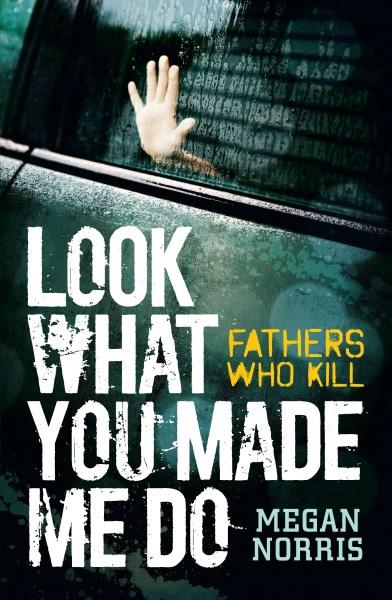

Megan Norris is a journalist who has written a number of true crime books, including one on the father in the dam story – the Robert Farquharson murders of his three sons, though from his wife Cindy Gambino’s perspective rather than the view Helen Garner took in House of Grief. In this book Norris covers seven cases of filicides where the father was the perpetrator; in one case the man was killed by police (he had also killed his wife’s father as well as the children), in three the fathers also killed themselves. The introduction gives an overview of the problem and some sobering statistics, and each chapter covers the relationships between the man and his partner—all failing or failed, many violent—mainly from the mother’s point of view, and with frequent references and quotes from media sources to whom the women and their family and friends later spoke to.

Review by Anne Buist

My Take: I read some true crime, most related to my topic of interest—parenting and families and the crime associated with them, an area I write fiction about and work in professionally. I found I read this book mainly with the latter hat on—perhaps it would be impossible not to. Anyone working in this area has to find ways to distance yourself from the trauma inherent in much of the work, or else it would be impossible to do (or write about). You need some distance to read this book as well—or else read over time rather than in two sittings like I did. It’s tough and gruelling reading—not because of the writing quality (which is solid)—but because of the material covered. It would be easy to think all men were untrustworthy violent assholes if you take these stories out of context (in more uplifting moments in the book we hear that at least in two of these stories the women have gone on to have another, good, relationship and have children).

Filicide, though we feel we hear a lot (the media reports them all and often in depth, at the time and then again at the Coroner’s inquest or/and court case), is actually rare. The chance of being murdered in Australia is highest in your first year of life—and biological mothers are just as likely to be responsible in these cases. Compare this to the risk of being murdered in the USA where it is astronomically higher if you are a black man between 18 and 40.

The purpose of books like Look What You Made Me Do should be about alerting us to early warning signs, improving police responses and legal avenues, not just in these cases but also for the much more common Domestic Violence situations. In this book, there are examples of where as a result there have been attempts to do this. In the best case scenario, maybe increased awareness can help women walk away before it’s too late and men take responsibility for their own issues. Certainly at least two of the female survivors have been given impetuous by their personal tragedies to work for better support and protection.

The common theme of this book, besides abusive homicidal men, is revenge against their partner as motive. It is certainly clear in several, though not all, that this was the driving force. What each of these men did was horrendous and inexcusable. And yet.

Perhaps because most true crime books I have read are dedicated to one case, I found with a case a chapter, the investigation didn’t go deep enough to really do the story justice. In two, the psychiatrists are quoted and an attempt is made to make sense of why these men went over the edge—after all, DV and unhappy custody battles are common, and filicide much less so. Some of these men appeared to love their children—and of course some were also suicidal. What was missing for me was this deeper level, maybe because any attempt to explain their behaviour might be seen as excusing it (I was sent hate mail when I suggested we needed to try to understand such perpetrators). The author was able to highlight where there were clear mental health issues in these men who for the most part seemed to have violence as the only way to deal with frustration and despair, and who felt they owned their partners and children. All totally unacceptable—but the flipside of the victim role that keeps women disempowered and unable to protect their children. Is there a way to identify them early (like at school)? Help them take responsibility for themselves while teenage girls are being helped to assert themselves and feel they deserve better? What was going on with them as children and could their parents have been helped to help them?

None of this is possible in a chapter per case…though some is hinted at. Worth keeping in mind as you read it.

My score: Solid writing, difficult stuff. 4 out of 5