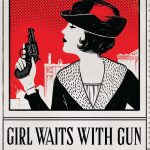

US crime author Amy Stewart spoke to Robyn Walton, national co-convenor of Sisters in Crime Australia, about her two historical crime novels – Girl Waits with Gun, and Lady Cop Makes Trouble (Scribe). Robyn will also be in conversation with Amy on 3 March in South Melbourne (details below)

Hello Amy. Thank you for making the time for this Q &A. As your two novels have been very well received and we have quite a few writers and would-be writers visiting our website, I’m going to focus my early questions on the “how-to” aspects of creating historical crime fiction based on real events and people. Then I’ll ask about social issues raised by your storylines.

As a natural sciences author and bookstore owner based in California, how did you come to be interested in law and order matters in New Jersey in 1914-15?

While I was researching my previous book, The Drunken Botanist, I ran across a story about a man named Henry Kaufman who was arrested for smuggling tainted gin. I thought I should do a little more investigation to see if Henry Kaufman went on to do anything else interesting. That’s when I found an article in The New York Times from 1915 about a man named Henry Kaufman who ran his car into a horse-drawn carriage driven by these three sisters, Constance, Norma, and Fleurette Kopp. They got into a conflict over payment for the damages, and it escalated from there.

The sisters received kidnapping threats, shots were fired at their house, and they were generally tormented for almost a year. I never did figure out if this Henry Kaufman was the same one who was arrested for gin smuggling, but I kept digging into the story of the Kopp sisters.

Once I compiled a short stack of newspaper clippings, I thought, “Well, surely somebody has written a book about the Kopp sisters. At least a little local history book, or a children’s book, or something.” I was amazed to find out that nothing had been written about them at all. There was no book, no Wikipedia page—nothing. They’d been completely forgotten about. I reconstructed their life stories from scratch.

Did you first try writing a non-fiction narrative? Or was an embellished, fictionalized version your choice from the outset?

Did you first try writing a non-fiction narrative? Or was an embellished, fictionalized version your choice from the outset?

I knew right away that this should be a novel, and that it should be not just one novel, but several. The problem with nonfiction (as I know well, having done a lot of it) is that you always have to be able to answer the “so what?” question. If I told you I was going to write a nonfiction book about New Jersey’s first female deputy sheriff, you might say, “So what? Why would I care about that?” People tend to decide whether or not to read a nonfiction book based first on what they think about the topic. Maybe they don’t read books about law enforcement, or books about women’s history, or sports, or nature, or whatever the topic might be.

But fiction doesn’t have that problem, exactly. You might read a novel about a French tennis player or a Depression-era schoolteacher or a Civil War doctor, and it wouldn’t matter so much if you’re not normally interested in tennis players or doctors. With fiction, we just don’t segregate ourselves by subject matter in the same way.

Also, there’s so much I don’t know about the Kopps. I don’t know what they talked about at home, or why people did what they did. Months and sometimes years go by when I don’t know specifically what the sisters were doing. Fiction lets me fill in those gaps.

Finally, it helps that their real lives break naturally into these episodic elements that work as individual novels. I’m writing about a fifteen-year span of their lives in which they were living and working together as three adult sisters. It’s one long story that has a beginning, middle, and end, and will take many novels to tell. So it’s a series in the sense that it’s going to be several novels about the same people, but it’s not a traditional crime series in the sense that each book won’t be about solving a particular crime. They happened to work in crime and law enforcement in different ways over the years, but the books are really more about them, and their work is just a part of it.

I’m fortunate that my publisher is very interested in the idea of these books taking different forms. They won’t always be told in first person from Constance’s point of view, for instance. The third in the series, which I’m finishing now, is told in the third person and is much more about getting into the lives of some of the women in the jail where Constance works. So they’ll be different kinds of books—different structures, different voices, different styles—all loosely hung on this true story.

Were there any authors whose books gave inspiration for how to devise a hybrid of non-fiction and fiction?

Not really. If anything, I try very hard not to read books that are similar to what I’m trying to do, because I don’t want to be overly influenced (or limited) by what other writers have done.

I was very influenced by Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series. I’d read many of those books over the years, but as I was writing Girl Waits with Gun, I started over and read every one straight through from the first to the last. He’s writing about an African-American man who’s struggling to get by in Los Angeles after World War II, and into the sixties and seventies. The historical backdrop, and the prejudice Easy Rawlins faces, is very much what those novels are all about. It doesn’t so much matter who committed the crime. Those books are all about how Easy Rawlins survives in the world he’s in—and how that world goes to work on him. Life really kicks Easy Rawlins around. He’s shaped by all the blows he has to withstand—not just the physical blows, but the hatred and prejudice and violence against him and his community.

And that’s what I’m doing with the Kopp sisters—I’m exploring how they survive, and who they become, in an era when social forces were really working against them.

What did you see in 35-year-old Constance Kopp and her two sisters that made you think they could be developed into engaging characters?

I really fell in love with Constance right away. I very much identify with her. As a 35-year-old, unmarried woman, six feet tall [1.8m] and 180 pounds [91kg], Constance must have felt very much like a misfit. I think we all feel like misfits in one way or another. And she really didn’t know her own strength until she went up against Henry Kaufman. I love the idea of this woman whose life is totally changed by a freak accident. And her sisters’ personalities are very much true to life—I was lucky enough to track down family members who could tell me more about what these women were really like. I thought it would be wonderful to write about three adult sisters who were living and working together—I can think of very few examples of that in literature.

Both novels are narrated in the first-person by Constance. It must have been very important for you as author to create an ongoing voice that was plausible, distinctive and consistent. How did you go about that and how long did it take to establish Constance’s voice?

Yes, I am always thinking about how Constance would say a particular thing. I wanted these books to sound spoken, not written, as if Constance were sitting in a chair and telling you about what happened. So I read each book out loud over and over to try to scrub any “written” language out of them. For instance, a person might write, “Walking across the street, I noticed the dog.” But nobody has ever said that aloud. You might say, “I saw a dog when I was walking across the street.”

So I worked on that, and I also worked on her choice of words and phrases. I read a lot of novels written in the 1910s—everything from Edith Wharton to Mary Roberts Rinehart, and obscure novels that have been digitized by Google—and I also read newspapers, magazines, and transcripts of speeches, courtroom testimony, and other such forms of public speaking. (Google has digitized a lot of books and periodicals that contain such transcripts.) I keep a long list of words and phrases that seem very particular to the time—words that have fallen out of use, or odd phrases we don’t use anymore.

I also use Google’s Ngram Viewer to check for anachronisms. It creates graphs of word usage over time, according to the works it has digitized. For instance, in those days, it was “lip-stick,” not “lipstick.” I’ve won some arguments with copyeditors thanks to Ngram, and I’ve also saved myself from some embarrassing anachronisms.

Finally, I put a lot of thought into how women spoke differently in those days. I have a home video of my great-grandmother talking to the camera for an extended period of time. She was born in Pennsylvania in 1905, and my characters were born in nearby states between 1878 and 1897. So she’s the only person I ever knew well who was more or less of that generation and region. I have watched that video over and over and thought about how she presented herself. She was very forthright, very direct, and spoke clearly and in complete paragraphs. There was no “um” or “like” or “so” as we do today. She took elocution classes as a girl and knew how to hold the attention of a room. I want Constance to sound like her.

Oh, one last thing: I’ve gotten to be friends with my audiobook narrator, Christina Moore. By a lucky coincidence, she grew up very near Paterson and Hackensack, so she does the accents very well. I have sent her manuscript pages and asked her to read and record them, so I can hear them spoken aloud by someone else. That really helps with dialogue.

Constance’s take on life is often droll, wry. And her sister Norma’s savouring of headlines is funny. No doubt you found some wit and whimsy in newspaper reporting, but it seems you have amplified the humour component?

I think humour is very hard to write, and almost impossible to do deliberately. If I happen to be writing and something makes me laugh, I keep it, and I might try to tweak it to make it more effective. I’ve spent some time studying the techniques of stand-up comedians, who I think are incredible wordsmiths. They think about language as carefully as poets do, but unlike poets, they get instant feedback—if they choose a slightly less funny word, they know immediately, because they don’t get a laugh. When I teach writing classes, I do talk about humour and I share the handful of tricks I know, but honestly, I think it either shows up on the page or it doesn’t.

Pacing and rhythm are common authorial concerns. Must a low-tech society and rural setting dictate a fairly slow pace with time for memories, repetitions and gradual build-up to revelations? Did you ever hanker for a faster tempo and more frequent moments of fierce action?

Honestly, I never thought about this. I’m far more interested in the emotional journey my characters are taking, and how they become who they are going to be over the course of the book. In Girl Waits with Gun, a car accident puts them in the path of a vicious man, but it also forces them to reckon with who they are, where they have been, and where they’re going next with their lives. Lady Cop Makes Trouble takes place over a shorter timeframe—about six weeks—and it’s less of a sprawling family novel and more of a chase. Constance has to catch a bad guy, but she also has to juggle the demands of her job, her family responsibilities, and the constant scrutiny of the press and the public. The point of the novel is not so much “will she catch the bad guy?” but “how is she going to make it as a woman doing a man’s job?”

The strengthening alliance and attraction between unmarried Constance and married Sheriff Heath is subtly suggested. For instance, in Lady Cop Makes Trouble the two are side by side at a children’s concert exchanging work updates in whispers. “He gave me the smallest smile and nudged my arm with his.” Do you have any advice for writers portraying an old-fashioned, polite, constrained relationship?

What I know about Constance and Sheriff Heath in real life is that they were obviously very important to each other. Sheriff Heath offered Constance the job that would change her life. Constance put him through a lot—he paid a steep political price for hiring her, but he always defended her and his decision. I know from other documents I have that they continued to be in contact over the many years that I will cover with this series.

I think that they had an interesting and, at times, charged relationship. Sheriff Heath saw something in Constance that no one else had ever seen, and he gave her a chance. That must have been a very profound experience for Constance. Sheriff Heath, for his part, found himself working with a woman who understood his job in a way that perhaps his wife did not.

In those days, it was so rare for men and women to work together. Today, we know how to have co-workers with whom we work closely and creatively without that turning into romance. In those days, men and women didn’t know how to have professional relationships. So I think it might have been confusing for both of them, but I also thought there was something magnetic between them. We’ll see this go back and forth over the years.

I don’t really know what to suggest to other writers about this—I mean, I think their relationship is a very particular kind of thing, and I’m just trying to portray it in all its complexity.

Fleurette, the youngest of the sisters, is creative, flirtatious and exuberant. She shows promise in fashion design and live performance. Constance sees her preoccupations as frivolous but funds them nonetheless. Do Fleurette’s inclinations tell us anything about existing and emerging possibilities for women in 1915?

Sure—Fleurette is going to be in her twenties in the 1920s, so she’s bound to be trouble. She’s much more of a modern woman than her sisters, and she’ll probably drag them into the modern age. At that time, there were a lot of societal fears about women being out in the world, enjoying more freedom, and perhaps being more in charge of their own sexuality and their own relationships. That’s definitely Fleurette!

In an op-ed piece in The New York Times (26 July 2016), you sketched the history of American women’s involvement in law enforcement. When the real-life Constance Kopp chased down a male suspect and cuffed him she was doing the work of a deputy sheriff; the sheriff who had hired her faced criticism. Your novels could be read as lobbying for women’s paid involvement in public life. You see a need to continue lobbying today?

I’m writing these books because these three women are so fascinating to me, and came to mean so much to me personally as I uncovered their real lives, that I decided to drop everything else in my life and devote myself to telling their stories. I simply want to write entertaining novels that people enjoy reading.

It is very true that even today, women are greatly under-represented in law enforcement. Women make up only 12 percent of sworn officers nationwide [in the US]. And women officers commit fewer acts of violence and brutality, so we clearly bring something valuable to the job. But I’m not writing novels to lobby for any particular thing to happen. That’s a sure way to kill a work of art.

Your novels acquaint us with horrible working and living conditions in silk factories, boarding houses, gaols, and so on. We hear of strikes (some with unintended negative consequences such as extended separation of young children from their parents). How do the 1910s measure up as a period of labour and institutional reform?

It’s a fascinating era, for the very reasons you mention—and there are so many parallels to today. The silk strikes came about because factory owners realized they could upgrade their equipment and have workers operate four looms at a time, not two. This new technology made them twice as productive and made the company more profitable, but the owners didn’t want to share those profits with the workers. Sound familiar?

Other issues that we’re still dealing with today, at least in the United States: immigration, war, technological disruption, income inequality, and how to best deal with the root causes of crime and poverty. It’s astonishing how little has changed, in some respects.

As an epigraph to Girl Waits with Gun you supply an excerpt from The New York Times in which Constance is quoted as saying “I got a revolver to protect us, and I soon had use for it”. In the epigraph to Lady Cop Makes Trouble Constance is reported to have hidden behind a tree for five hours “waiting to get a shot at a gang of Black Handers who had annoyed her”. With modern America suffering many gun deaths, do you have any thoughts on gun ownership rights, restrictions, etc.?

I am as anti-gun as a person can possibly be, and I only wish we were more like Australia in that respect. You’ll notice that Constance doesn’t actually shoot anyone or even use a gun to detain anyone. She fires it a couple of times to scare somebody off, but that’s about it. This is a true story and she did carry a revolver. Also, Girl Waits with Gun is a wonderful alliterative headline and book title. But I’m not interested in having Constance go around shooting people.

Thanks so much for your responses.

Amy Stewart will join Australian crime author Lesley Truffle and compere Robyn Walton on a panel at Sisters in Crime, 8 pm Friday 3 March at the Rising Sun Hotel in South Melbourne. Click here for more details and bookings.