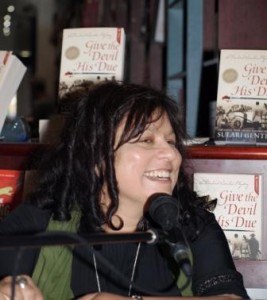

Sulari Gentill was interrogated at Readings Hawthorn on 9 November by fellow author and Sister in Crime Angela Savage for a gripping and often hilarious 40 minutes about her latest book, Give the Devil His Due, the 7th Rowland Sinclair mystery. If you missed the event (and lots did), catch up with Marc McEvoy article published by Fairfax Media today.

For immigrants from temperate climates, the heat of their first Australian summer can feel relentless. Sulari Gentill was almost seven years old when she arrived in Melbourne in 1977 with her family, Sri Lankan immigrants who had moved first to England and then spent five years in Zambia while the embers of the White Australia policy were cooling.

Gentill remembers lying on the lawn with her two sisters outside her brick veneer house in Noble Park on hot summer nights while their father, who had brought them to Australia for a better education, told stories about the stars blinking above them.

“It was too hot in the house and my father used to describe the constellations, with Greek mythology woven in,” says Gentill, a former lawyer who now writes crime novels.

“So, right through childhood I’d look up at the stars and I’d be filled with a sense of wonder. I thought it meant I should become an astrophysicist.”

That childhood dream almost became a reality. Gentill’s family moved to Brisbane, settling in the riverside suburb of Yeronga, but after her schooling Gentill relocated to Canberra to study at the Australian National University. It wasn’t what she expected.

“I went off to uni to study astrophysics and to my great disappointment, they told me my beautiful constellations were just balls of gas that were defined by mathematical formulas,” she says.

“After a year I moved to law simply because I was so disillusioned I had to look for a subject that had no maths in it.”

Gentill’s transition to law was writing’s gain. While working as a corporate lawyer for water and energy companies, she discovered she had a skill in storytelling.

“Law is very much a storytelling profession. When you explain a contract to a client you often resort to story. The better you can make your story, the more likely you are to get them to agree.”

About six years ago, she decided to try her hand at fiction. It was more accident than design. She had no lifelong ambition to be a writer and her first attempts were young-adult fantasy adventure stories that drew on her knowledge of the classical mythology taught to her by her father.

They were eventually published in 2011 and 2012 as a series called The Hero Trilogy.

However, Gentill’s latest book, Give the Devil His Due, is her seventh novel in a historical crime fiction series set in 1930s Australia that was picked up in 2010 by independent publisher Pantera Press. The first, A Few Right Thinking Men, was shortlisted for the 2011 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for best first book. A Decline in Prophets, the second, won the 2012 Davitt Award for best adult crime fiction.

Like all the books in the series, Give the Devil His Due follows the exploits of Rowland Sinclair, a wealthy gentleman artist turned amateur sleuth who lives in a Woollahra mansion where he entertains bohemian friends including the object of his passion, sculptor Edna Higgins, and his friend Clyde Watson Jones, who is handy with his fists. Sinclair’s political leanings are obvious. His greyhound is called Lenin.

In the new novel, Sinclair, a keen driver who plans to race his Mercedes at the Maroubra Speedway, is embroiled in a murder mystery after a journalist who has interviewed him turns up dead.

As in any good whodunit, there are plenty of twists and turns, including a dip into the occult.

Real-life figures also play a part: actor Errol Flynn, artist Norman Lindsay, Smith’s Weekly reporter turned “Witch of Kings Cross” Rosaleen Norton, and even Arthur Stace, author of the ubiquitous “Eternity”, written in chalk around the city. To add a feel for the times, each chapter opens with a real cut-out from publications such as The Sydney Morning Herald.

Like Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher mysteries, Gentill’s stories are part of a growing interest in Australian historical crime fiction. Sinclair even has a touch of the eccentric chivalry found in Arthur Conan Doyle’s bohemian detective Sherlock Holmes.

Gentill decided to write stories set during the 1930s because her husband, Michael, a history and English schoolteacher who helps edit and research her work, was frustrated with reading subjects he knew little about in her fantasy stories.

“Initially it was a very pragmatic decision to make the change to set my stories in the 1930s,” she says. “Michael’s a boy from the country and he’d get caught every time he came up against a name like Agamemnon or Achilles, complaining that they would stop his enjoyment of the manuscript. So one day he says, ‘For God’s sake, Sulari, can’t you write something with names like Peter and Paul in it?’ ”

Gentill breaks out laughing. “Of course I ignored him at the beginning but I realised I had fallen in love with the craft of writing, and when I write I become completely immersed in what I am doing, which is fine for me, but it’s hard on your partner. So I went looking for something pragmatically, to bring Michael into my head.”

As a historian, Michael’s area of expertise is the extreme right-wing movement in Australia during the 1930s. Gentill read his thesis and realised it would make a fascinating backdrop for a novel.

The recurring villain in her series is the historical figure Eric Campbell, a World War I veteran turned lawyer who established the the right-wing New Guard, which was tied to the fascist movements in Germany and Italy. Other members included Captain Francis de Groot, who beat Premier Jack Lang to cutting the ribbon at the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. (D.H. Lawrence’s novel Kangaroo is partly about the Old Guard, the anti-communist group from which the New Guard split in 1931).

“As I dug into it, the 1930s entranced me because of its position in our history,” Gentill says.

“Coming off the 1920s, Australians were angry and disillusioned, open to new ways of thinking as the old mores fell away. But the 1930s led to World War II and that intrigued me. It seemed to be a time when Australia was deciding who it was.”

Gentill says the period has parallels with Australia today, particularly after the global financial crisis. “We live in a sort of shadow of what happened in the 1930s after the Depression,” she says.

The public’s impotence over the treatment of asylum seekers is a case in point.

“That happens because people get distracted by just living. You see things that are wrong. You say, ‘That’s not right. I object to that. That’s not compassionate. That’s not humanitarian.’ But you get distracted by paying the electricity bill and driving the kids to school and so on.”

Gentill, who is 44, writes at an astonishing rate, completing a novel in three months. She and Michael live with their two sons, Edmund, 14, and 10-year-old Atticus (named after the protagonist in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Gentill’s favourite book), on a 25-hectare property on the outskirts of Batlow, a town of 1500 in the foothills of the Snowy Mountains.

They bought the farm 16 years ago when Gentill had to commute from Tasmania, where she worked as lawyer. It meant being separated for long periods but they had a strategy for the future.

They planted oak trees, added 50 tonnes of lime to their soil and cultivated French black truffles, the culinary delicacy. After four years, the first truffles sprouted on the oak roots and they now run a successful truffery, doing truffle runs every week during winter, sometimes in the snow by moonlight.

Gentill says that living away from city lights provides a wonderful view of the stars and, as her father did for her, she talks to her sons about the constellations.

“I thought when I told them about mythology and stars that they’d switch off, thinking, ‘There goes Mum again’, but they listen. When you are out in the country and you look up at the Milky Way, you feel the immensity of the universe.”

Gentill’s favourite constellation is Orion. “I love it because it is so easy to pick. You look for the saucepan in the sky and sound very learned when you cry, ‘Look, there’s Orion’.”

Give the Devil His Due is published by Pantera Press at $29.99.

And another thing: Gentill learnt to speak English in Zambia but her parents made it her primary language only after emigrating to Australia.

Info: http://www.sularigentill.com/; https://www.panterapress.com.au/shop/category/11/sulari-gentill