Marele Day famously – and successfully – takes literary risks. Her crime fiction won her a lifetime Ned Kelly Award and a Shamus Award; her non-fiction book How to Write Crime won another Ned Kelly and her best-selling ‘literary’ novel, Lambs of God, is now an award-winning miniseries (Binge). Other works include a fictionalised biography (Mrs Cook: The Real and Imagined Life of the Captain’s Wife) and the story of a Buddhist monk (The Sea Bed).

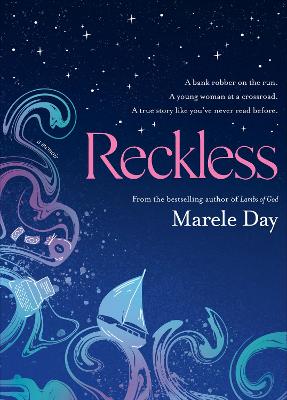

Now for the first time, Marele puts herself on the page. Reckless blends memoir, adventure, and crime, and explores the nature of risk and friendship. In it Marele writes about her past, her friendship with the ‘shapeshifter’ Jean Kay, and her investigation into his part in a multi-million-dollar heist.

Marele spoke to Sydney member and author Natalie Conyer.

Marele, what brought you to this book? Why did you decide to write it?

Reckless represents a significant departure in my writing. I’ve never before been interested in writing memoir. What appeals to me about writing novels is the journey of exploration – into the imagination, into a fictional world, travelling through uncharted territory. I had already ‘travelled’ through my own life once by living it. Why go over it again by writing about it when I could go somewhere new? Also – and this will come as no surprise to anyone who knows me – I’m a very private person. Did I really want all my softer tender parts, my human frailties on display? No.

Then something happened. My partner became seriously ill and so began a harrowing few years. My partner has recovered, but that visceral presence of death, the reminder that we are all terminal cases, summoned up the big existential questions – what did I want to do with the time that was left, what did I want to leave behind? Now instead of being reluctant to even contemplate telling my story, I felt a great urgency to do so.

The book has an astonishing, prismatic structure that examines both the narrator’s life and the life of her friend, Jean. It skips around in time and subject, only to return again and again to certain motifs. Why did you choose this structure and how hard was it to achieve?

The book deals with doubles, dualities, twos – my double vision that’s introduced in the first chapter, two main protagonists – Jean Kay and Marele Day, our two ‘adventures’ – the sea voyage that ended in near shipwreck, then later me investigating and writing about the heist Jean was involved in, my younger self and more mature self, the past and the present, so it made sense to have a weave of narrative strands and to move between them. For this book, there was no appeal in keeping to a strict chronological order – this happened then this happened. Reckless is a memoir and its structure more closely mirrors how memory works – events in the present trigger memories of the past.

Past and present are inherently there in most crime writing. The forward-moving story is an investigation of something that happened in the past. The initiating incident in a crime novel e.g. a dead body on page 3, is the climax of a story that has already taken place. As the narrative moves forward the investigating character comes across clues – artefacts of the past – and puts the story together. So, this patterning was familiar to me. Moving around from one narrative strand to another in Reckless allowed me to have more control over when to reveal and when to withhold, to hopefully create page-turning suspense that I’d learnt from writing crime fiction.

The biggest challenge was moving from one strand to another seamlessly, and at the appropriate moment in the storytelling, to make the segues appear to be natural and effortless. It took a lot of hard work and several drafts to get it right. I could probably write another book with the material left on the cutting room floor!

Reckless is part-memoir, part-reflection, part-biography, and partcrime novel. As a crime novel, it bypasses all the usual genre conventions, yet investigates deeply the nature of crime and its effects on people and society, both at the time of the crime and after. What does this book have to say to more traditional crime writers?

Crime genre embodies Darwinian principles of survival – diversity in the species and the ability to adapt to the changing social environment. It has amazing resilience and elasticity. There are rules but they can be bent or broken. We have seen this over the last thirty years or so in the array of protagonists the genre has produced and the diversity of stories being told. We seek the comfort of the old and the thrill of the new. Readers of crime expect a crime to be committed and that during the course of the story the writer will supply the answers to the questions surrounding it – the how-why-who-where-and-when of it. That’s the comfort of the old. The thrill of the new is how-why-who-where-and-when the writer fulfils those expectations.

Be bold, be brave in your writing. Write the book you want to write.

This is the first book in which you’ve put yourself on the page. What did it feel like, and how was it different to write without the remove of fiction?

I discovered that words provide a protective armour for the soft squishy bits, the tender raw emotions, and that storytelling can transform the random messiness of life into something shapely.

In writing fiction my main concern is for the characters, to tell their story as best I can, but this time I was much more aware that I was writing for an eventual reader. The memoir became a letter from writer to reader, a trusted friend I could reveal myself to.

More on Marele Day and her books here.