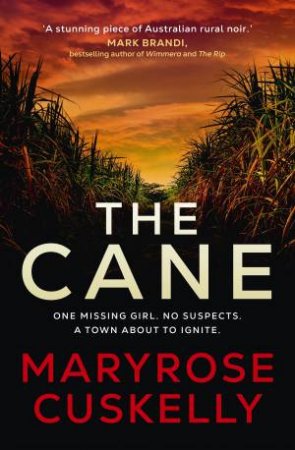

Despite my last two books sitting firmly within the crime genre— the most recent one fiction (The Cane), the earlier one non-fiction (Wedderburn)—I didn’t set out to become a crime writer. In fact, I actually tried to avoid it; not on account of any disdain for the genre, but because I wasn’t sure I had the writing chops for it, particularly when it came to fiction.

I began researching the triple murder in the small Central Victorian town of Wedderburn mainly as a way of getting past the disappointment of another writing project falling over. A friend, as a way of moving me on from the writerly funk I had fallen into, reminded me that her father was a good friend of a man who, although he had confessed to killing his three neighbours, was determined to plead not guilty to murder at his trial. The promise of access to someone close to the killer was enough to get me interested in the story. My book Wedderburn: A true tale of blood and dust was the result.

Even after Wedderburn was published, I didn’t really consider myself a crime writer. I had happened to write a story about a crime, but it was also a book about grief, the legal process, resilience, and the complexity of social hierarchies in rural communities.

When I first submitted the manuscript of what was to become The Cane to Allen & Unwin, I avoided the term crime. Yes, there was a crime at the heart of it, but it was primarily a coming-of-age story, I insisted to my publisher. She raised an eyebrow. Perhaps with a touch of Australian gothic, I conceded.

My publisher demurred, as did my editor. “It’s crime,” they both told me. Furthermore, they added, if I knew what was good for me, I would lean more heavily into the conventions of the genre. They suggested I tone down the manuscript’s gothic excesses, simplify the overly episodic structure, and bolster the plot. So, I did. (Obedience wouldn’t seem to be the most useful attribute for a crime writer, but there you go.)

I think my reluctance to accept my identity as a crime novelist, sprang from something in my creative process. I must confess that I’m not hugely motivated by plot, which, let’s face it, is the meat and potatoes of most crime fiction. My writing projects usually begin with a mood or a feeling rather than a strong narrative. There is something tenuous, internal, and instinctive about the process. An image emerges, sometimes just a blur of movement in my brain that, as I try to define it, stays slightly out of focus. I inch closer and gradually its edges resolve to the point where I feel I can grasp it. Eventually, the image becomes more substantial, developing a sense of weight that I carry around with me. (I know I’m in trouble with a writing project when I lose the ‘feel’ of it in my chest.)

Initially, with The Cane, I wanted to retain that sense of the esoteric, perhaps more ‘literary’ vision I had of the novel. What I found, of course, was that those crime conventions—building suspense, a propulsive plot, presenting several possible suspects—all helped carry and strengthen those aspects of the novel that remain important to me and can still be found within it.

Who knew?

Maryrose is speaking on Sisters in Crime’s live online panel, Small Towns, Big Crimes! Friday 25 February October, 8pm.