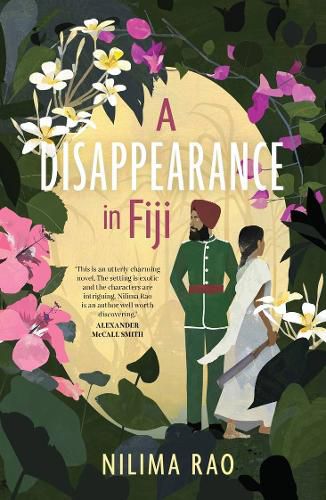

My debut novel, a historical crime fiction novel titled A Disappearance in Fiji is set in Fiji in 1914, which is a fairly unusual time and place to set a novel. I am often asked – why Fiji, why 1914? The setting is of particular significance to my family. In researching and writing this novel I have learned of the sacrifices made by my great-grandparents, that led to the privileged life that I now enjoy.

In 1914, Fiji was one of the newer colonies of the British Empire, having ceded sovereignty to the Queen in 1874. Slavery had been outlawed in the British Empire, and to fill the gap of cheap labour required in the colonies, a system of indentured servitude had been set up, sending Indian labourers all over the world, from Trinidad to Mauritius and many other colonies. In the case of Fiji, approximately 60 000 Indians went to Fiji to work in the sugar cane plantations. This is how my great-grandparents went to Fiji.

The Indians who signed up for this program were poor, often indigent, and generally illiterate. They would sign contracts to work for five years in a particular colony. They theoretically signed the contracts of their own free will but, of course, their illiteracy and their often desperate circumstances left them vulnerable to exploitation. Add to this, the fact that the agents who were recruiting them to the indentured servitude program were paid by the number of people they recruited. They profited by lying to the people they were recruiting, who had no way of knowing what was actually written in the contracts they were signing.

There are numerous stories of the lies and fraud employed to get people up, lies ranging from the type of work to even simply where Fiji was. People thought they were going somewhere near Calcutta, only to be sent halfway around the world. And crossing the ocean, the kala pani, the black water, was taboo in Hinduism, leading to a loss of caste.

A particular vagary of the system was in relation to the proportion of women being sent to Fiji. Initially, the ships were exclusively full of men. For what was also a de facto resettlement program, only sending men was clearly not going to work. A rule was added – for every hundred men, forty women had to be sent. How this rather strange proportion was arrived at is a mystery unto itself. Now there was a new challenge for the unscrupulous recruiters – how to get enough women onto the ship for it to be allowed to leave. This is when the stories change from merely lies to actual fraud, blackmail, and intimidation, forcing women onto the ships.

These stories are all anecdotal, there is no data available to understand how many of the 60,000 went under duress or with a distorted view of what they were signing up for. But the volume of anecdotes builds an overwhelming narrative of exploitation that seems to have been largely accepted. There was an outcry in India about this program, and it was finally halted, with the last ships arriving in Fiji in 1916.

As to the experiences of the Indians when they arrived in Fiji and entered their indentured servitude, that is a whole other story!

More info here.