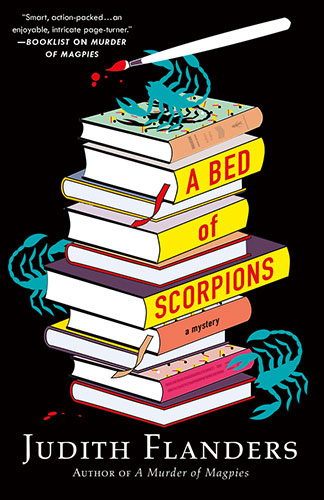

Author: Judith Flanders

Publisher: Alison and Busby

Copyright Year: 2015

Review By: Robyn Walton

Book Synopsis:

What’s an editor to do with so many demands? Do you deal with the morning’s pile of manuscript submissions first? Or the swine from sales who steals all the chocolate digestives? Or do you concentrate on your ex-lover, whose business partner has just been found dead in their art gallery, slumped over his desk with a gun in his hand? It’s another day at Timmins & Ross publishing house, but when sharp-tongued editor Samantha Clair’s CID boyfriend is brought in to investigate Frank Compton’s death, her loyalties become stretched. And when one of Aidan Merriam’s artists is found dead in identical circumstances, Sam takes on the art world and the CID, armed with nothing more than her reliable weapons: satire, cynicism and a stock of irrelevant information culled from novels.

If you’ve read Judith Flanders’ first novel, A Murder of Magpies (originally published under the title Writers’ Block), you’ll already know her protagonist, Samantha (Sam) Clair. Sam works in book publishing in contemporary London and when not oscillating between wisecracks and self-deprecation she’s something of a trouble magnet. This time around, trouble arrives in the form of a dilemma familiar to crime fiction readers: a man has been found shot dead in his office, with a gun and a suicide note to hand, and while it looks as if he killed himself there are suspicions.

The deceased, Frank, was joint owner of a commercial art gallery, and Sam is rapidly drawn into the world of art trading courtesy of an improbable number of links. First there is her long-standing friendship with the dead man’s business partner, Aidan. Then there is her relationship with CID inspector Jake Field, who’s investigating the death. Sam’s mother has been Aidan’s lawyer for 20 years and knows a rich art collector or two, so she too is embroiled. A subplot in which Sam labours to prepare a presentation on subsidies in commercial publishing also serves to keep her attention on the gallery death case, thanks to overlapping personnel and interests. Additionally there’s the fact that Sam likes the collages of an American Pop artist named Stevenson, whose works are sold in the UK by Aidan’s gallery. Stevenson’s skeleton was recently discovered; it had a gun and a suicide note with it, but there remains uncertainty as to whether Stevenson really killed himself.

When Sam is knocked off her bicycle in a hit-and-run incident, she wants to think it was an accident. Pointing out her multiple connections to the gallery death, detective Jake argues it may have been a deliberate attempt to kill her. Yet the top police have decided to halt the investigation, and the forensic accountants have declared the gallery’s books clean. Why is it then that, as Jake remarks, ‘every loose end in this case returns to money’? And why should Sam be anyone’s target? Soon the discovery of the gallery’s art restorer dead in his studio raises still more questions.

In the final chapter Sam is trapped in a life and death confrontation with the prime wrong-doer. She swallows her usual impulse to voice smart-arse comments, while realising that the fact she is still capable of mental sarcasm is helping her stay calm. With the baddie obligingly confessing, explaining the background to the interlocked crimes and the research required, Sam thinks: ‘Just what the world needed, a murderer with a library card.’ After a few more unspoken witticisms, Sam manages to escape harm, and those loose ends are quickly sorted.

Like the previous Sam Clair novel, A Bed of Scorpions is essentially a tale of financial crime, with human greed and other frailties propelling the scheming, and human deaths and injuries mere collateral damage. However this second novel has a little more heart than the first. Sam is just as smart-mouthed as before, but this time around she lets herself express some sympathetic emotions. When Aidan miserably tells her of his business partner’s death, Sam is responsive: ‘I slid around to his side of the table and sat close, holding his hand. Human warmth won’t drive way death, but it doesn’t hurt.’ As in the first novel, Flanders’ plotting is not easy to follow. However, improvements in Flanders’ characterisation of the various schemers, suspects and bystanders, and the attaching of feelings to characters, helped this reader stay with the story.