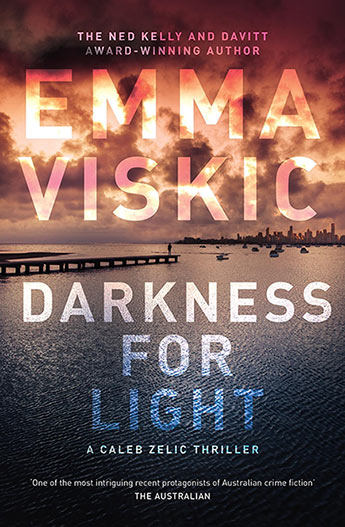

Author: Emma Viskic

Publisher/Year: Echo/Bonnier/2019

Publisher overview

Reviewer: Robyn Walton

Emma Viskic’s novels featuring private investigator Caleb Zelic have been most memorable for the likeable and touchingly fallible character of her protagonist. In book three, Darkness for Light, Caleb is back in Melbourne, handy to his pregnant wife, Aboriginal artist Kat, and again stumbling into controversial zones.

Viskic continues to blend her dark content with whimsy and humour. The opening chapters of the new novel illustrate the technique. Having decided to concentrate on safe white-collar fraud investigations, Caleb isn’t fazed by an invitation to an inner-urban children’s farm for a clandestine meeting. He discovers his suited prospective client murdered. Police arrive, one with an unhelpful goatee “like a half-eaten rabbit”.

With the deceased revealed to be an undercover federal police officer, Caleb is involuntarily linked to organised criminality under scrutiny by a federal taskforce. And when another federal cop violently assaults him and threatens him with prosecution, he feels pressured to do what she demands: locate his absent business partner, the double-crossing Frankie, who’s said to be in possession of wanted documents. Caleb is hampered and endangered, however, by the feds’ need-to-know approach. Knowledge isn’t just power but also protection, he muses.

Caleb’s secondary case takes him into a restaurant that smells “like deep-fried happiness” and is run by a multi-generation family using sign language, with customers also Auslan users. As Caleb mostly uses lip reading plus hearing aids, he is not a representative member of this capital-D Deaf community, but his access into it enables Viskic to observe the politics of cultural identity. Readers may be prompted to find out more about the emergence of a proud community of people who value their deafness as a cultural marker rather than a disability or pathology, are resentful of paternalism, and expect protection of their rights.

Readers new to this series may find the staccato quality of Viskic’s prose jarring. Words are omitted. Sentences resemble truncated thoughts. Exchanges are direct, even seemingly blunt and abrupt. Visuals and body language supplement words. I suspect this prose style serves several purposes: it hurries the action along, when read aloud it has its own percussive musicality, and it complements the customary communications style of some in the Deaf community.

Published on 8-9 February 2020 in The Weekend Australian and reproduced with permission.