The first crime book I ever encountered was The Elephant and the Bad Baby, the 1969 picture book by Elfrida Vipont, illustrated by Raymond Briggs. Alright, it’s not exactly marketed as such, but it’s about a crime spree through a village by a giant elephant and a so-called bad baby. The elephant steals ice creams, pork pies, lollies and fruit — going rumpeta rumpeta rumpeta all down the road, as the famous refrain goes — with irate shopkeepers in pursuit. Up on the elephant’s back, the baby enjoys these spoils until it all becomes too much and he asks to be taken home to his mother, who smoothes everything over by making pancakes for everyone.

It’s great fun, but like all good children’s books there’s more to it than that. For example, the fact that the baby is described as Bad from the moment we meet him, without any evidence. And the way that the elephant deflects attention away from his crimes by pointing out that the baby has “never once said please”. Give this to an overthinking child and they start behaving like a defence lawyer: “Why is the baby’s criminal history relevant?” “Where’s is the proof that the baby is ‘Bad’?” “This elephant is guilty of incitement!”

We start to grapple with social and personal values from a young age, so it’s little wonder that crime fiction is so popular with children. Crime fiction allows them to think about ‘the rules’ and what it means to break them, as well as how to be a ‘good’ detective who hunts for evidence and outsmarts the ‘bad’ villain. As they get older, children are capable of thinking about the nuances of crime, the shortcomings of justice systems, and the truth about growing up in an environment where certain crimes are more likely to occur.

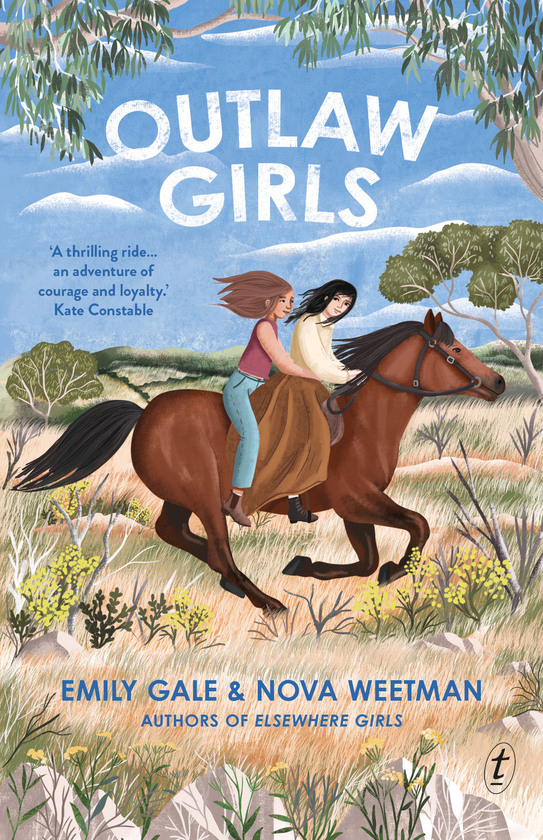

The complexity of criminal behaviour is one of the themes my co-writer Nova Weetman and I loved exploring in Outlaw Girls, our time-slip novel in which one of the central characters is Kate Kelly, younger sister of the Australian bushranger and gang leader Ned Kelly. Kate’s perspective and her role in the gang’s two-year run has rarely been explored, in fiction or otherwise. Researching her life, we realised how much our readers would relish the opportunity to examine this famous story as Kate — a girl who loved her outlaw brothers dearly.

We wanted readers to ask themselves lots of questions while Kate was tearing around the Victorian high country on horseback. Such as, what would I do if I were Kate? Would I help my brothers, accused of murder? Would I risk my neck by breaking the law? What would I think of my brothers’ actions, the police, the courts, and public opinion?

It’s exciting and rewarding writing for the middle-grade age group, which can range from 9 to around 14 years, because of how ready they are for complex characters and challenging social environments. And, also because we know how much children enjoy moral and legal reasoning, and deconstructing notions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

Children start to question things long before they hit school age — just as I questioned the rumpeta rumpeta rumpeta crime spree of the elephant and the Bad Baby (but was he really bad?) As middle-grade writers, Nova and I think the crime and mystery genre can learn as much from young readers as they learn from our books. This multifarious genre richly deserves those young and curious minds, and vice versa.

More info here.