Have you noticed a quiet revolution happening on your bookshelves and television screen? I’m talking about the rise and rise of the older woman amateur sleuth.

Twenty years ago, I would have been pressed to name more than Miss Marple as an example, but now we have Elizabeth and Joyce from the Thursday Murder Club, the new Marlow Murders team in the books by Robert Thorogood, Agatha Raisin in the books by MC Beaton, and Susan Ryeland in the Magpie Murders series, to name just a few.

Of course, the professional older woman police detective has graced our books and screens for a good fifty years or so. I still remember the furore in 1991 when Helen Mirren brought Lynda La Plante’s uncompromising character Jane Tennison to life in the TV version of Prime Suspect, Here was an older woman as a Detective Chief Inspector and more importantly as the protagonist of the story. For far too long, the older women characters we read and saw on screen were adjunct to a male protagonist—mother, aunt, nosy neighbour, wife, and more often than not, victim. With Jane Tennison we got a competent and fully realised older female character who had come up through the ranks the hard way and gave as good as she got. And boy, did the 1990s’ critic boys have a lot to say about that!

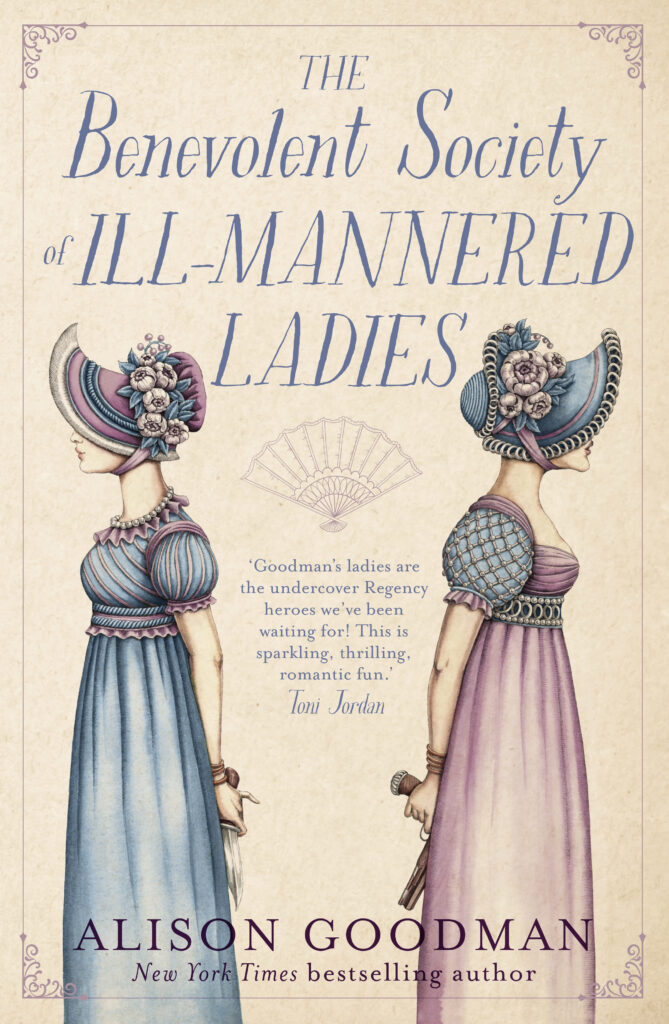

DCI Tennison paved the way for Ann Cleeves’s D I Vera Stanhope, gruff and compassionate and resolutely ignoring her age, and Vera opened the doors for more excellent older police women in books and on TV. And with them came their amateur counterparts, two of whom are my own characters, Lady Gus and Lady Julia, in my Regency-era mystery, The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies.

So why are older women amateur sleuths becoming so popular? It is, I think, a complicated question. The answer would have to explore reader demographics (who is reading crime fiction and driving demand), the ebb and flow of particular markets, and where manuscript purchase money is targeted (Young Adult fiction was having a golden age but now crime fiction—particularly the cozy crime novel–is booming), the number of older influential actresses looking for good parts, and the state of gender and age politics, particularly in an ageing population. I don’t think the answer can be found in a short blog—it could, in fact, be a PhD research question–but I can offer some thoughts about why I now write older female sleuths.

Until recently, I have been writing young teenage female protagonists in various genres––crime, fantasy, and science fiction––and enjoying it thoroughly. Then I hit my fifties. Along with menopause and far less tolerance for idiots came a realisation that I wanted to write characters who had more self-confidence, life experience, and definitely more older woman attitude. I wanted to write characters who reflected my own mid-life-stage and all the glories and imperfections that came with having lived forty-plus years on this earth.

I am revelling in the chance to write older women as protagonists. Lady Gus and Lady Julia are forty-two and are not adjuncts to a main male character. They are not the wife, the victim, back-story mothers, or nosy neighbours. They may be dismissed by the world around them, but they are driving the story and using their wits and life knowledge to help other women in trouble. And that is what I want to read and watch: clever older women solving crimes by using skills and knowledge they have developed through their lives. Skills that are often scoffed at but prove invaluable in the amateur sleuthing game: empathy, interrelationship know-how, and the ability to not give a damn about what other people think. And, of course, the occasional well-aimed kick in the groin. My guess is that there are a lot of other readers out there at the same mid-life stage who are eager to see themselves reflected in the fiction they read.

In a world that seems to be tipping towards the dark and violent misogyny, it is comforting to see older women in books and television series making a difference. Yes, it is fiction, but when we see ourselves in our stories, then we see the possibilities within our reality. The older woman is no longer going to be overlooked. She is not invisible or the adjunct to someone else’s story. She is centre stage and she is brave, wise and ready for action.

More info here.