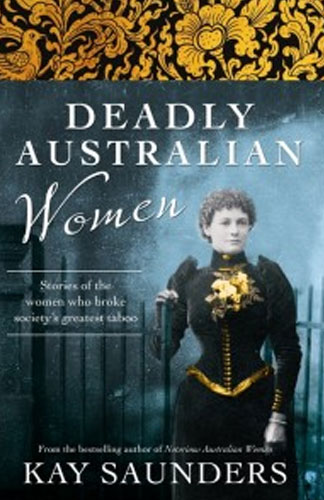

Author: Kay Saunders

Publisher: ABC Books – Harper Collins Publishers

Copyright Year: 2013

Review By: Sylvia Loader

Book Synopsis:

Do women kill? Yes they do, but often for very different reasons from men … Meet the women who have murdered – they’ve killed children, husbands, lovers, relatives and friends. They include the desperate, the poor, the abused, the sexually betrayed, and the downright callous. In some cases they were motivated by fear of society’s disapproval, in others they acted to save themselves from violence.

Among their number were early backyard abortionists like Madame Olga and Madame Harper; poisoners like Caroline Grills and Yvonne Fletcher; women who committed infanticide like Keli Lane; women who formed lovers’ pacts to murder their husbands; and women whose troubled lives on the margins, like transgendered Eugenia Falleni/Harry Crawford, led them almost inevitably to crime. In her first, bestselling book, Notorious Australian Women, author Kay Saunders profiled some of the country’s most scandalous women. Here she turns her eye to those who have broken one of society’s most cherished taboos and become both notorious and deadly.

This excellent book is a factual presentation of some of the killings that have been committed by women during the history of Australia. They have been grouped into categories, many of which are derived from the female reproductive system. These include the cases of women dying after an illegal abortion performed by a woman, and the killing of babies and children, both by their mothers and by the notorious baby farmers. The cases are presented without sentiment and with details of the investigations and trials, together with the names of the judges and lawyers involved. It is amazing how many of these are familiar in both criminal and political contexts.

There is a chapter devoted to poisoners, supposedly the female method of choice, and others to the killing of spouses, abusive or otherwise, in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Some chapters are devoted to one woman, the most recent of whom is the baffling case of Keli Lane. Kay Saunders makes the point that Keli, like many other women, has never admitted her guilt.

Another is that of Eugenia Fallen, or Henry Crawford, the name she used during her “marriages” to two women. The trial reeked of voyeurism.

Even in a scholarly work like this, characters can emerge. My particular favourite was Caroline Grills, the homely middle-aged woman who smiled throughput her trial and was sentenced to death in 1954 for thallium poisoning. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and Grills lived for another six years, taking a maternal interest in the younger prisoners and offering them advice. By them she was affectionately known as “Aunt Thally”.