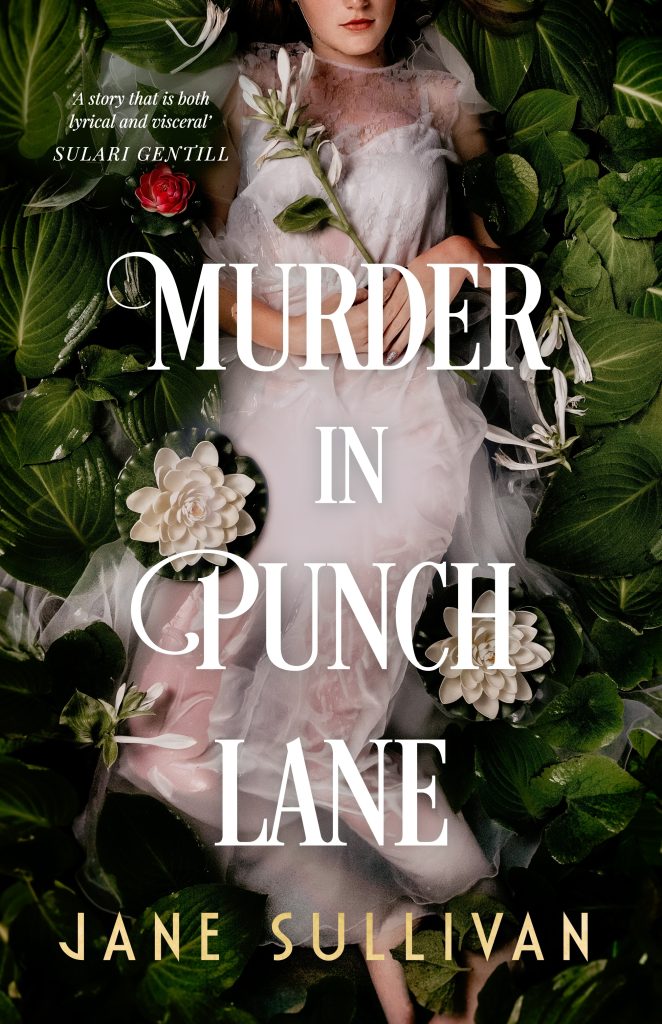

For the August Author Spotlight, Narrelle M Harris spoke with author and literary journalist, Jane Sullivan about her debut crime novel, Murder in Punch Lane.

Murder in Punch Lane was inspired by the historical life and death of young actress, Marie St Denis, in Melbourne in 1868. What about Marie drew you in to write about her death?

It was the obituaries that did it. Marie died tragically young, only 17, of a laudanum overdose. I read the newspaper obituaries of the time and though they were full of melodramatic pathos, there was also a very consistent snide note. They implied she was either a fallen woman who had died of unrequited love, or a megalomaniac who identified too closely with the tragic heroines she played. I became very indignant on poor Marie’s behalf. And I began to imagine: What if it wasn’t suicide, as everyone assumed? What if it was murder?

Your Melbourne of 1868 is moody, dangerous and full of hidden (and not so hidden) vice beneath the gloss of a wealthy, growing city. Was it really as debauched as that?

Yes, I don’t think I have exaggerated. Of course the official accounts only mention a prosperous, thriving, God-fearing city. But there are also hints and gossip in other accounts that suggest this was a veneer over much darker goings-on. Journalists such as Marcus Clarke chronicled the city in all its guises, much as Charles Dickens did in London, and Clarke wasn’t afraid to show you the down and outs, the poverty, the crooks, and the hypocrites.

The ‘Samsons’ of your book – Marie’s lovers, all powerful men in Melbourne in the 1860s – are either real men of the time or characters inspired by real people, representing the police, the judiciary, religion, medicine, the theatre, and politics. How do you walk the line between real people and their invented versions in these books? What rules (if any) have you set for yourself?

This has been quite a challenge, but a very rewarding one. I read about the real prominent people of the city so I could get a good idea of what they were like. Where the facts ended, I felt free to invent. I tried not to give them any traits or actions that would be outrageously out of kilter with what we know about them. Actually, I got quite fond of Sir Redmond Barry the judge, Walter Montgomery the actor-director, and Sir Frederick Standish the chief police commissioner, even though I made up awful things for them to do.

Where I’ve departed a bit further from the facts, I’ve changed the character’s name or created a composite character, such as my hellfire preacher. I absolutely loved James Neild the theatre critic and coroner, who inspired my character Edward.

How do these men represent Melbourne of the era you’re depicting?

They were all men (naturally) of extraordinary power in their different fields; they all knew each other; they all had great ability and noble ambitions for their city or their profession – but they also had human failings that could see their visions compromised or corrupted and could lead to callousness and cruelty. And God help anyone who got in their way.

How does flaneur/journalist/wannabe-hero Magnus fit into that picture?

Magnus is based very loosely on the young Marcus Clarke, journalist, and man about town, raffish and charming, always profligate and precariously on the edge of poverty but pulling himself up out of the pit each time. Clarke’s engaging, irreverent, and often funny accounts of Melbourne life in all its variety were one of my chief sources. Journalists could move between high and low society in a way few others could. There’s a wonderful photograph of young Marcus Clarke in riding boots and a rakish hat manspreading himself on a chair. That swagger and cockiness I gave to Magnus.

Your actress-detective Lola Sanchez is a beautifully realised and textured character: tough and clever; ambitious and vulnerable. How do you feel she embodies or reflects the times and setting?

I was thinking about how actresses could survive in a culture that worshipped and celebrated the successful ones as celebrities but at the same time regarded them as no better than sex workers, who were stigmatised as the lowest of the low. I guessed there would have been a lot of Harvey Weinstein types in the theatre world at that time. To survive, you’d have to be both very talented as an actress – which would mean you’d be empathetic and vulnerable – and also very tough, wily and determined.

Lola finds out very early what men can be like, so she mistrusts them. That doesn’t save her from the likes of Walter Montgomery. But her determination shows up in her quest to find the murderer of her dear friend. It’s her way of fighting back.

In researching your novel, what was your favourite or most surprising discovery?

I set my murder in Punch Lane, a tiny little street in Melbourne that’s now a cool place near the theatres with modern apartments and bars. Back in 1868, it was very seedy. At the end of all my research, I discovered that there had actually been two murders in Punch Lane, very shortly after my fictional one. One of them was a sex worker who killed another sex worker with an axe because she kept calling her mother a whore. Both of them were very drunk. The murderer confessed and was sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to 21 years in jail. An awful bloody crime, but you could also see both of those women as victims of their times.

Another delightful discovery was a breathless confession in a secret diary that the Chief Commissioner of Police had held a dinner where naked ladies sat on black velvet chairs so everyone could admire the whiteness of their flesh. Of course that led to a vital scene in the book.

Murder in Punch Lane, like your 2011 novel Little People, is a mystery set in the theatrical world of 19th-century Melbourne and drawing on real personalities of the day. What brought you back to this setting? Do you think you might return to it?

I have been fascinated by 19th-century Melbourne since I came to live there in 1979. You can still see so much of the old city when you walk around its streets. In between the glass office towers, there are many proud Victorian edifices – banks, pubs, town halls, theatres – sometimes a little worse for wear but still celebrating the brash gold rush days that created the wealth to build them. And in the narrow lanes with their cool graffiti and edgy bars you can still imagine a darker, shabbier, more dangerous place where thieves and cut-throats lurked.

Melbourne doesn’t feature in the book I’m working on now, but there’s a good chance I might return to that place and time. There’s still so much that inspires me.

You’ve been in the UK researching your next novel: any links this time with crime, the theatre, or Australia?

Well, it’s in around about the same period, but I think it will be set entirely in England and in India. No crime, no theatre, but some very theatrical characters, again inspired by real people. And there is a somewhat remote Australian connection, as I’ve just discovered. I visited the poet Tennyson’s house on the Isle of Wight and it turns out his son Hallam (who looks like Little Lord Fauntleroy in the boyhood pictures, with long hair and a velvet suit with frilly collar) grew up to be Governor of South Australia, and later the second Governor General of the whole of Australia. This was at the turn of the century, about Federation time, and apparently, he did a really good job.

You’re a literary journalist, writing about books for major newspapers. What’s it like to be on the other side of that relationship, with your own fiction?

A bit weird! I’m generally very comfortable writing about other authors and their books and saying what I think, but I can’t really say what I think of my own books: I’m far too close to them, I can’t step back. One thing that writing fiction has done is to give me enormous respect for other writers of all kinds of books, because I know what an incredibly hard thing it is to do at all, let alone do well. So I’m very reluctant to dismiss books and very keen to write about the ones I admire and love. Reading is such a special pleasure and I’m determined to infect others with my own enthusiasm whenever I can. And authors need lots of readers to buy their books.

More info here.