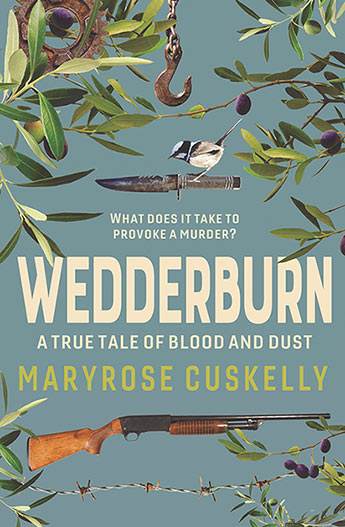

Author: Maryrose Cuskelly

Publisher/Year: Allen & Unwin/2018

Publisher Synopsis

The story of a grisly triple murder in Central Victoria in October 2014 – contemporary Australian true crime at its best

‘An ugly story told beautifully. WEDDERBURN will hold you tightly in its grip, and leave an imprint when it lets you go.’ Myfanwy Jones

‘In WEDDERBURN, we see the trauma caused by the blackest of hearts. A desolate yet deeply affecting tale of savage crime in rural Australia.’ Mark Brandi

‘Maryrose Cuskelly has the rare gift of telling a true story with the excitement and vividness of fiction; she never forsakes the facts in this chilling and hypnotic book.’ William McInnes

‘The slaughter was extravagant and bloody. And yet there were people in the small town of Wedderburn in Central Victoria who, while they did not exactly rejoice, quietly thought that Ian Jamieson had done them all a favour.’

One fine Wednesday evening in October 2014, 65-year-old Ian Jamieson secured a hunting knife in a sheath to his belt and climbed through the wire fence separating his property from that of his much younger neighbour Greg Holmes. Less than 30 minutes later, Holmes was dead, stabbed more than 25 times. Jamieson returned home and took two shotguns from his gun safe. He walked across the road and shot Holmes’ mother, Mary Lockhart, and her husband, Peter, multiple times before calling the police.

In this compelling book, Maryrose Cuskelly gets to the core of this small Australian town and the people within it. Much like the successful podcast S-Town, things aren’t always as they seem: Wedderburn begins with an outwardly simple murder but expands to probe the dark secrets that fester within small towns, asking: is murder something that lives next door to us all?

Reviewer: Jane E Lee

You’ve got to feel sorry for true-crime writers these days.

Just think of the grim Darwinian struggle they face to catch our attention. Not only are the shelves of bookstores (real or virtual) swamped with the constant deluge of new product, but we addicts can increasingly get a fix from our choice of other media, whether TV and movies (Underbelly; Spotlight) streaming services (Making a Murderer) or podcasts (Serial). And the juicy details of crime or arrest can flash around the world the very day of the events.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that, in trying to pique our interest with her 2018 book Wedderburn, freelance writer and editor Maryrose Cuskelly has set herself a doozy of a task.

After all, the facts of the killings she writes about are well-known – and have been since the night of the crime. On a hot spring evening in 2014, the then 64-year-old Ian Francis Jamieson clambered through a fence on his rural Victorian property to confront his neighbour Greg Holmes, 48, and attacked him with a knife. Leaving his victim dying on the ground, Jamieson then returned home to gather two firearms, crossed the road to the house of Holmes’ mother and stepfather, Mary and Peter Lockhart, and shot the couple, both in their seventies, to death. After this he calmly called 000 and confessed.

Although Jamieson later tried to plead “not guilty” to murdering Holmes, there has never been a question of “who-dunnit” about any of the killings.

How then to capture and hold the reader?

Cuskelly’s approach is to make her book a “why-dunnit.”

One aspect of the crimes that cries out for explanation was what prosecutor Andrew Tinney called “their extravagant and exceptional brutality.” Holmes was stabbed 25 times; both the Lockharts, dying or dead, were shot at close range in the groin – and Jamieson reloaded three times. But the angle that really drew media attention was the apparent motive: Jamieson was reportedly furious that dust had been drifting onto his property when the Lockharts used an access road to cart water from Holmes’ land.

Sherlockian powers of deduction are not needed to conclude there must have been more to the story than that. Cuskelly’s book is a meticulous exploration of what that “more” might have been.

In her clear, vivid prose, she paints an unsettling picture of a dangerous situation involving difficult personalities and the fraught psychodynamics between them. This was not just a dispute over “a bit of dust.”

To uncover the story, Cuskelly follows the time-honoured drill for a true-crime writer. She attends court, she reads transcripts. She meets with families, friends and acquaintances of both murderer and victims. She speaks with local officials and police. At a couple of points she nods in the direction of scholarship, touching briefly on useful academic concepts: British neurosurgeon Henry Marsh’s thoughts on the “illusion” of a single, unified self; the notion of “catathymic homicide” – a “sudden, unprovoked killing where the perpetrator often can’t articulate a logical reason for the murder.”

But most of all, as she discusses killer and victims with those who knew them, she forms tentative opinions, modifies them, revisits them. She shares those opinions with us.

Cuskelly has been criticised for this. One reviewer commented that she “makes this at least as much her story as that of the people who were there.” But I found the documenting of her reactions enlightening.

Detached, clinical analysis is one way of trying to understand what drives someone to kill. Before reading Cuskelly’s book, I had seen the chapter on Ian Jamieson in The Mind Behind the Crime (Macmillan, 2018), the second of two excellent books by psychologist Helen McGrath and journalist Cheryl Critchley. McGrath’s take on Jamieson is helpful as far as it goes; she concludes that he has paranoid personality disorder – but labelling is not explaining.

What we really want to find out is this: if Jamieson had a personality disorder, what was it that, in his seventh decade, made him kill these victims, in this way, at this time?

Cuskelly is our guide in this quest. On one level she’s just an honest broker retailing – conflicting – community input on how Jamieson could have “suddenly snapped.” On another she’s unavoidably an interpreter. We can’t go and interview the good folks of Wedderburn ourselves, or form a firsthand view of their mindsets and biases, so Cuskelly does it as our proxy. The avowedly personal nature of her responses, paradoxically, frees us to form our own independent theory of the crimes.

There are a couple of small flaws in the book.

Cuskelly cites general “notes and sources” for each chapter, but I would have liked to see precise references footnoted – for example, where she appears to be quoting from emergency services recordings or police interviews. An index would also be helpful for anyone who wants to compare the accounts given by different people or cross-reference incidents in the book.

But these are minor issues. Overall, and surprisingly, given the scenario Cuskelly had to work with – a known killer, already convicted – Wedderburn held my interest to the end. The book goes a long way to explaining the inexplicable in circumstances where those who know the whole story are either dead, or, in the case of the perpetrator, not talking. (Jamieson didn’t respond to Cuskelly’s attempts to contact him in prison). In these post-modern times, when we’ve been taught that “truth” is a social construct, we know the most we can hope for is a painstakingly assembled, perforce subjective but – with luck – illuminating “glimpse of what lies beyond this tale of murder, grief, cruelty, obstinacy and hard-headedness.”

Cuskelly’s book gives us such a glimpse, and a satisfying one at that.

.