2016

SidHarta Publishers

Reviewer: Kerry James

Synopsis

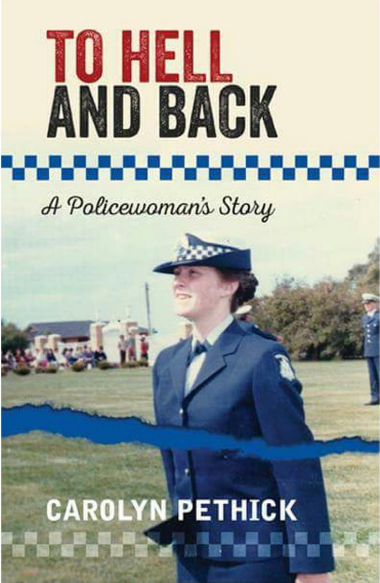

To Hell and Back’ is a memoir detailing one policewoman’s trials and tribulations working within the ranks of the Victoria Police Force from the early 1980’s to the present day. Despite numerous instances of harassment, false accusations and character assassinations, the member still manages to maintain her sanity and perform her policing duties to the best of her ability. Ultimately, this is a story about one person’s struggle to say and do the right thing, to follow procedure, no matter what the eventual cost to herself or her career.

Review by Kerry James

A policewoman’s story’, To Hell and Back, might be a salutary lesson for all women who dare to retaliate against men’s bullying in male-dominated professions. It is brave, impassioned, and, ultimately, a sad and frustrating read.

Pethick was a most successful cop by all her accounts until she joined a station where a senior male officer made her life so difficult that she filed a complaint for bullying against him. Thus begins a sorry saga of red tape, of help promised within the system and not given, a malevolent Acting Superintendent, who blocked the action, and the women, who abetted him.

There are heroes: police officers who supported her throughout; and villains, who sought to put the image of the Victorian Police Force first. Pethick is not shy in calling, the Chief Commissioner Christine Nixon to book for failing to implement her much-vaunted ‘open door policy’ as her non-responses to Pethick’s increasingly desperate cries for justice mount, and her health and the happiness of her only daughter suffer. She is denied promotion and finds that the Ethical Standards Division has charges against her of so serious a nature that they could result in her dismissal or even imprisonment. Over time, her distress becomes so great that she becomes ill and heads to Work Cover.

In the end it appears that it is an error by the ESD which should never have happened or been allowed to get so far had the personnel involved for a crucial six months not acted ‘like sheep’ (p.136). It is a sadder and wiser woman who writes of her beloved Police Force,

‘Once again the Police Department would never admit they were wrong. They would never admit they had made a mistake. … I know they would find something, no matter how trivial, to make certain that I would come out of this mess as the guilty party. The Police Department and especially the Ethical Standards Department were never wrong. I knew from all my years in the police force that neither would ever apologise. … No, they would dig as deep as needed to make certain that this was all my fault (p.130).

Pethick returned to work in an office capacity, determined not to raise her head above the parapet again, and retired in 2016 after almost thirty years of service. Her sister also apparently resigned from the force because of bullying. So, what have we gained since the 1980s when this fresh-faced high achiever achieved her dream of becoming a policewoman when she was just twenty-one?

This is not an easy read as much of it concerns bureaucratic rules and regulations within the forces and consists of emails as details of meetings and charges are hashed out. We, the readers, also are not in a position to independently verify most of this material, although there is no reason to doubt Pethick’s account, and it can make for passages of dry verbiage. A list of chapters and an index would have been helpful, even though almost all of the names have been changed to protect the ‘good guys’.

Pethick was almost broken by the systematic wrongs done to her. The final outcome was small comfort. ‘It was just an administrative error. Legally you cannot do anything about it,’ she was told. But this slim volume is her testament and it may serve to help others caught up in similar situations.