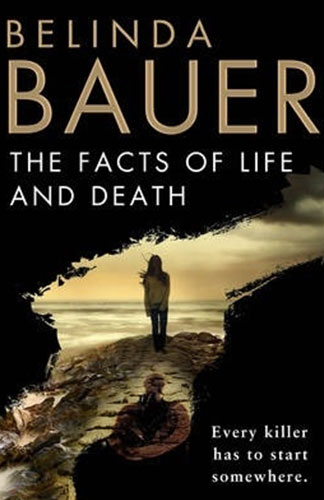

Author: Belinda Bauer

Publisher: Bantam/Transworld

Copyright Year: 2014

Review By: Robyn Walton

Book Synopsis:

Call your mother.’

‘What do I say?’

‘Say goodbye.’

This is how it begins.

Lone women terrorised and their helpless families forced to watch – in a sick game where only one player knows the rules. And when those rules change, the new game is Murder.

Living with her parents in the dank beach community of Limeburn, ten-year-old Ruby Trick has her own fears. Bullies on the school bus, the forest crowding her house into the sea, and the threat of divorce.

Helping her Daddy to catch the killer might be the key to keeping him close.

As long as the killer doesn’t catch her first…

Around the villages of the North Devon coastline a serial killer is at work. Typically the perp lures a teenage girl or young woman into his car late at night after she has missed the last bus. He takes her to a deserted outdoor spot, where he forces her to strip naked and use her iPhone to call her mother and say goodbye. While the distressed mother pleads for her daughter’s life, the call is cut off. And then either the victim is murdered by suffocation or, as happens in a couple of cases early in this novel, she escapes to tell the tale. This is a scenario presumably written with an eye to television or cinema: it’s lurid and exploitative. The level of emotional concern for the victims is low since the reader scarcely gets to meet them before they are abducted. We know and see no more of them than the obsessive and opportunistic killer does; as the narrator puts it at the start of one grab-and-kill episode: ‘Steffi Cole was almost home when she stopped being a person and became a means to an end’. As in most serial-killer stories, the murderer’s identity and motivation are eventually revealed. It comes as no surprise that long-established, mother-related bitterness and blaming have driven this man’s viciousness toward ‘whores’.

Why read a book with such a misogynistic character driving its narrative? Well, Bauer writes exceedingly well about family relations and socio-economic strata from the point of view of children and young people, and in this book the majority of the storyline is told from the viewpoint of a naïve ten-year-old, pre-pubescent Ruby. In the course of the narrative Ruby’s mother will explain the ‘facts of life’ to her; and with Ruby’s father being one of the local men who’ve formed a vigilante posse to watch out for the serial killer, the girl is also learning about the reality of death — hence the novel’s cumbersome title. It’s exciting for Ruby when Daddy calls her his Deputy and lets her come out with him in the car when he’s on patrol.

Bauer also writes about places perceptively, commonly imbuing them with a dark and sinister feel. With Ruby and her parents subsisting in a deteriorating rented cottage in a rat-infested hamlet confined at the base of a steep hillside between the encroaching sea and the damp forest, Bauer sets the scene for a tumultuous denouement. As a storm roars and the hamlet is inundated, Ruby – by now menstruating and conscious of her transition into womanhood – must first flee to higher ground to stay alive and then, in a melodramatic climactic scene, pick up a weapon to save herself a second time.

Bauer can be funny too. If you’re wondering about the absence of police protection for vulnerable girls and women in this part of England, you’re right to be concerned. Bauer’s representatives of the Devon and Cornwall constabulary are far from proactive. The more engaging of the duo charged with the investigation is a 24-year-old seriously distracted by his girlfriend’s wedding plans, which she is pushing forward although all he really longs for is ‘a Korean gangster flick and a meat-feast pizza all to himself’. ‘As well as trying to catch a serial killer, on Tuesday night Calvin had held Shirley’s hand through a tablecloth crisis. … Shirley had turned Calvin’s flat into her own little incident room, swirling with a thousand paper samples and cloth samples and cake samples … It was a glittery tide of wedding porn’. Calvin’s superior officer, DCI King, is a brisk and wryly humorous woman but is not given enough page space to develop as a personality or solve the crime. I doubt either cop character has the ‘legs’ to return in another North Devon mystery, should Bauer decide to write one. Ten-year-old Ruby, on the other hand, is a memorable discoverer of good and bad truths.