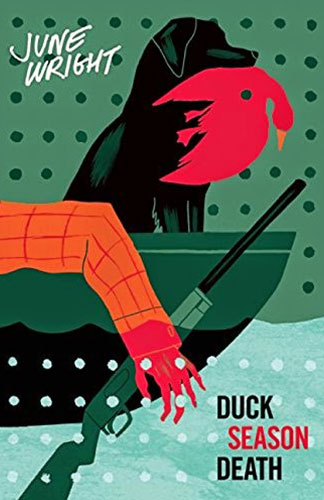

Author: June Wright, with introduction by Derham Groves

Publisher: Verse Chorus Press

Copyright Year: 2015

Review By: Robyn Walton

Book Synopsis:

When someone takes advantage of a duck hunt to murder publisher Athol Sefton at a remote hunting inn, it soon turns out that almost everyone, guests and staff alike, had good reason to shoot him. Sefton’s nephew Charles believes he can solve the crime by applying the traditional “rules of the game” he’s absorbed over years as a reviewer of detective fiction. Much to his annoyance, however, the killer doesn’t seem to be playing by those rules, and Charles finds that he is the one under suspicion

Duck Season Death is set in and around The Duck and Dog Inn near the Murray River in northern Victoria. If like me you find hunting of wildlife repulsive, don’t worry too much about whether this novel will advocate duck-shooting and dwell on the cruel details – it doesn’t. The annual autumn gathering of a motley band of shooters, most of them regulars, is simply the set-up for an Australian version of the classic house-party whodunit.

As an author with a growing familiarity with the publishing scene when she wrote this novel in the mid-1950s, June Wright amuses herself in much the same way J. K. Rowling, writing as Robert Galbraith, does in her second Cormoran Strike novel, The Silkworm, in which the London literary world is portrayed as luridly grotesque. Wright’s primary victim is a widely disliked older man, Athol, the publisher of an Australian literary magazine he regards as an “astringent influence in an uncultured society”. When he is shot dead whilst out shooting ducks, he is in the reluctant company of his nephew Charles, the magazine’s crime fiction reviewer. Charles, “in spite of his absorption in fictional crime”, realises the killing is not accidental. Informed of the death by Charles, the inn-keeper is facetious: “What a bad shot you must be! Or was it with intent? […] Perhaps an enraged author shot Athol by mistake for you.” With his fellow guests equally unsympathetic and the local police sergeant and doctor obtuse, Charles decides he must be the one to investigate, and as you’d expect his approach is to apply what he has learned in crime books. He is not helped by the woman who tells him she reads his reviews but never reads crime fiction.

Setting up Charles as her bumbling investigator, Wright is able to be self-consciously and wittily explicit about the succession of conventions she is playing around with: the “ill-assorted group weekending at a country house”, the guests so riled by Athol that “everyone was about ripe for murder”, the possibility of the culprit emerging from “this contrived setting”, the risk of “some female” interfering with clues, evidence (the bullet removed from the body) being discarded, a background of threatening notes and phone calls. There is even a suggestion of supernatural happenings, to which Charles shoots back: “There’s been enough breaking of the rules of the game as it is. Vengeful ghosts would be the ruddy limit.”

Each fresh suspicion or outright accusation spawns another, with traditional moral rights and wrongs increasingly displaced and lines of reasoning increasingly convoluted. So, for example, when Charles airs his notion that, years earlier, Athol had killed his wife by poisoning her, sexy model Margot is unsurprised: “She was a dreadful drear, you know, and she held the purse strings. A ghastly thing, but you really can’t blame Athol, can you?” Margot’s callousness leads Charles to the theory that it was Margot who poisoned Athol’s wife, so that Athol would then marry her, but then, with Athol having refused to remarry, it must have been Margot who shot Athol. Soon enough Charles himself is a murder suspect. And in the final chapter it falls to a proper detective to reveal how Charles has been fooled by the real murderer.

With most of the characters unlikeable, all of this play with conventions can become tiresome unless you’re an enthusiast of farce, the crime fiction genre and the postmodern mode – and Wright is certainly a proto-postmodernist. You won’t close the novel feeling cosily satisfied on an emotional level, despite the romantic kiss (”long and efficiently” carried out) at the end, but you may well admire Wright for her skills in plotting and send-up. When Wright submitted this novel to her publisher, three readers recommended rejection, all citing the manuscript’s use of stock crime fiction conventions as a demerit; the cleverness inherent in Wright’s deconstructive enterprise seems to have either escaped them or left them cold. Wright’s alternate title for her manuscript was The Textbook Detective Story. It’s a title which pretty well indicates both the book’s strengths and shortcomings.