In case you missed Jane Cadzow’s wonderful article from Good Weekend, on 16 January 2016, here it is: “Donna Leon and the madness of Venice”

Millions of readers, including our own PM, have fallen for mystery novelist Donna Leon’s blockbuster Commissario Brunetti series. But it’s not her proudest achievement.

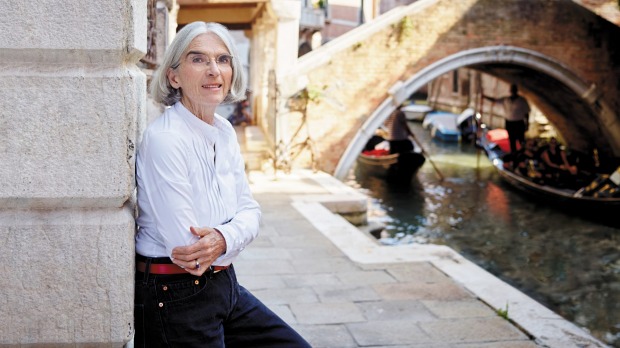

Donna Leon steps out of the busy restaurant into a damp Venetian night. A small woman with an alert, angular face, she pauses for a moment to consult the map imprinted on the mind of every long-time resident of the city. Then she sets off across the rain-slicked expanse of the campo and heads confidently into a maze of dimly lit alleys.

Leon’s novels could give you the impression that Venice is a dangerous place for an evening stroll. Stabbings, stranglings, shootings, suspicious accidents … Bodies pile up at a rate that distracts from the gorgeous scenery. (What’s that in the canal? Another corpse?) In real life, as Leon is the first to point out, the crime rate is extremely low. Since settling here more than 30 years ago, the American-born writer has heard of only two assaults in the streets. “Venetians are not a violent people,” she says, sounding a tiny bit disappointed in them.

Celebrity often incites special treatment, and that’s bad for a girl, don’tcha think?

Leon, 73, is published in 34 languages and has millions of fans around the world – among them Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. When asked on ABC TV what he liked to read on summer holidays, Turnbull said: “My favourite books on the beach are about Venice. So either John Julius Norwich’s histories or Donna Leon’s Commissario Brunetti detective books.”

Guido Brunetti, who made his first appearance in Death at La Fenice in 1992, is a warm-hearted, world-weary, intelligent cop. His ability to crack cases often seems of secondary importance: it’s his company that we readers like. And his beat.

The travel writer Jan Morris has described Venice as “half eastern, half western, half land, half sea … somewhere between a freak and a fairytale”. Its shimmering strangeness tends to overwhelm visitors (“Streets full of water. Please advise,” columnist Robert Benchley famously cabled to his New York office), so it is good to have Brunetti as our guide. As he wends his way through the labyrinthine laneways, passing domed churches and crumbling palazzi, skirting the Accademia, crossing the Rialto, ducking into a neighbourhood bar for a coffee and tramezzino, we not only soak up the splendour of the ancient metropolis but learn where the locals buy their fish and dump their garbage.

Such is Brunetti’s popularity that an industry has grown up around him. Visitors clutch copies of Brunetti’s Venice: Walks with the City’s Best-Loved Detective. They take home Brunetti’s Cookbook. A German production company has made 20 Commissario Brunetti telemovies, which Leon assures me are “pretty bad”. She reconsiders. “No, they’re not bad. They’re very, very German.”

Leon receiving a German literature prize, the Corine, in Munich in 2003; her crime novels have been turned into a German television series. Photo: Snapper Media

Not that she minds much either way. She doesn’t watch them – she has never owned a TV – and has no involvement in translating the novels to the screen. According to one of her friends, Toni Sepeda, Leon’s attitude is cheerfully mercenary: “She goes, ‘Here’s the book, give me the money, thank you, goodbye.’ ”

Sepeda, who conducts “Brunetti’s Venice” tours, has known Leon since the early 1980s, when both began working as lecturers in literature in the University of Maryland’s European division. “Donna was always reading murder-mysteries,” Sepeda tells me. “I was always saying, ‘I don’t know why you’re wasting your time on those. I’m reading Tolstoy and Shakespeare and Homer.’ Well, who’s laughing all the way to the bank now?”

Murderers aren’t the problem in Venice. Tourists are. Millions of them arrive each year, surging in eager waves into Piazza San Marco, swarming through the Doge’s Palace, squeezing onto the water-buses, known as vaporetti, that ply the Grand Canal.

Leon has a long-held policy of escaping the city in the warmer months, when the crush is at its worst, but it seems to her that the tourist season is now practically year-round, and that for the dwindling number of permanent residents (58,000 at last count, down from 120,000 three decades ago), living in Venice feels increasingly like camping out in a theme park.

In A Noble Radiance, Brunetti attends a funeral mass for a young Venetian in the 16th-century San Salvatore church. Sitting in a back pew, the detective listens with grim amusement to the whispered conversations of the huddles of foreigners who have come to see Titian’s Annunciation over the third altar on the right. The painting is mentioned in all the guidebooks and they are desperate to photograph it. “But during a funeral? Perhaps, if they were very, very quiet and didn’t use the flash.”

Like Brunetti, the otherwise good-natured Leon has slowly lost patience with the invading hordes. As her publishers prepare to celebrate this year’s release of the 25th Brunetti book, she admits she finds herself spending less and less time in the city she writes about so evocatively. The night we meet for dinner, she has just come from Switzerland, where she has the use of a friend’s apartment in Zurich and a house of her own in an alpine village near the Italian border. It is the time of year when she would normally be returning to Venice for the winter, but she says she isn’t sure how long she will stay: “It depends how many of them are in the streets.”

Too many, as it turns out. The next communication from Leon is an email saying she is again in Switzerland. “I sort of snapped,” she says, explaining that she retreated to the mountains after realising “that the boats were always crowded, that the main streets were impassable, and that I arrived home in a bad mood after being out”.

She isn’t the only one at the end of her tether. “Just last week,” she writes, “a friend of mine, a man of infinite calm and charity, said that he grows almost violent when he goes walking on the streets. If he sees a couple walking towards him, hand in hand, he insists on walking through them if the street is narrow. I think we are all corrupted in our characters or behaviours, like rats when there are too many of them in the cage. Luckily, I have yet to begin eating the newborn.”

Leon’s novels sell well in Switzerland, but she can go about her business undisturbed there. “Everyone is invisible in Switzerland,” she has said. In Venice, she is regularly bailed up by people in the grip of Brunettimania, many of them from German-speaking countries (“The centre of the cult is Austria,” she says). Venetians themselves leave her alone because, at her insistence, the books aren’t published in Italian.

I have heard she made this decision because she was concerned her frequent references to Italy’s endemic corruption could cause offence. Not true, she says. “If you read the Italian crime writers, you will see that they say far more critical things about the country.” No, the real reason is that she enjoys anonymity, preferring to be known to her Venetian neighbours as the friendly American who chats to the fruit-seller rather than the famous expatriate writer. “Celebrity often incites special treatment, and that’s bad for a girl, don’tcha think?”

The whole thing started as a joke. One night in 1989, Leon went to Venice’s opera theatre, La Fenice, to see a friend conduct a rehearsal of Donizetti’s La Favorita. Afterwards, they gossiped backstage about an internationally acclaimed but widely unbeloved conductor who had recently died. Soon the conversation turned to methods that might be used to murder a maestro in his dressing room, and it occurred to Leon that this might be a good starting point for a novel.

In Death at La Fenice, the career of a world-famous conductor with a Nazi past ends abruptly – between acts two and three of La Traviata – when he drinks a cup of coffee laced with cyanide. Leon put the manuscript in a drawer and left it there for a year. Then a friend insisted she enter it in a competition, which she won. Since the prize was a two-book publishing contract, she felt obliged to produce a second Brunetti mystery. Before she knew it, she had embarked on a third, then a fourth, though she still wrote the books for her amusement as much as anything else. (For editing the first three, she paid her university colleague, Toni Sepeda, in prosecco.)

Even now, Leon is reluctant to take her oeuvre overly seriously. Having spent the first part of her life studying and teaching the great works of English literature – the title of her doctoral dissertation was The Changing Moral Order in the Universe of Jane Austen’s Novels – she sees herself as a peddler of light entertainment rather than a purveyor of deathless prose. Far from sweating over the construction of watertight plots, she makes up her stories as she goes along, never knowing when she begins what the ending will be. If there is a knock at the door, she is as interested as her readers to find out who will come through it. I tell her this is amazing to me. “It’s amazing to me, too,” she replies.

A large part of the appeal of Leon’s books lies in the fact that her principal characters are so charming, and lead such nice lives.

In the first novel, she described Brunetti as “a surprisingly neat man, tie carefully knotted, hair shorter than was the fashion; even his ears lay close to his head, as if reluctant to call attention to themselves. His clothing marked him as Italian. The cadence of his speech announced that he was Venetian. His eyes were all policeman.” Brunetti is the antithesis of the stressed-out, fast-food-eating workaholics with terrible personal lives who populate standard police-procedurals. Happily married to Paola, a professor of English literature and a brilliant cook, with whom he has two delightful teenage children, he rarely stays late at the office or – heaven forbid – arrives early. There is no need, because so much investigative work is done for him by his boss’s secretary, Signorina Elettra Zorzi, a glamorous computer genius who hacks effortlessly into government files, Swiss bank accounts and so on.

Mid-morning, Brunetti might pop out for a glass of prosecco. At lunchtime, he goes home for a meal of, say, sea bass baked with fresh artichokes, lemon and rosemary. The family’s apartment is at the top of five flights of stairs, with views over the Grand Canal from the terrace. Brunetti, who relaxes by reading Greek and Roman history, discovered after he and Paola bought the place that the previous owners had built it illegally, simply adding another floor to an existing building. The one blot on his happiness is the niggling fear that someone in the city administration will find out about it: “The bribes would be ruinous.”

Leon has had accommodation problems of her own. For several years, she lived opposite an elderly woman whose TV blared at deafening volume all day and night, making it near-impossible for anyone in the vicinity to get to sleep. The neighbour ignored repeated requests to turn down the sound. “I could have wrung her neck,” says Leon, who instead had a woman who fitted her description bashed to death with a blunt instrument in Doctored Evidence, her 13th novel.

We don’t actually witness many killings in Leon’s books. By the time Brunetti arrives, the yellow tape has gone up around the crime scene. “I’m as one with Aristotle on this,” Leon has said. “Do the bloody deed off-stage and then have the messenger come in and describe it.”

She was appalled by the savagery of the violence against women in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the global best-seller by the late Swedish journalist, Stieg Larsson. (She didn’t read the next two books in the trilogy.) “Disgusting!” she says, leaning across her plate of pasta. “An absolutely disgusting book.”

She doesn’t like to criticise a fellow crime writer, particularly a dead one. “Poor guy. But the book is pathological. Sex is seen in that book as a weapon – only a weapon. It’s all about power.” She pauses. “Nobody has any fun.”

The pursuit of a good time has always been high on Leon’s list of priorities. Perhaps it’s in her genes. Her father was “a pretty happy-go-lucky guy”, she says. Her mother? “A lunatic. God, she was funny. One of the funniest people I’ve ever known … I think about her very, very often. I only have good memories. I know it’s very fashionable to have a tormented childhood, but I was cheated out of that.”

Growing up in New Jersey, Leon was the kind of conscientious kid who finished her homework before she went out to play (as an author, she delivers manuscripts on time or even early). But as she grew older, she realised she was completely devoid of ambition. “I just wanted to have fun.” After finishing university, she accompanied an old schoolfriend to Italy and found an entire nation in tune with her philosophy. “I was just blown away by it,” she says. “By the food, by the coffee, by the people. By how pretty the people were. They’re the most beautiful people on the planet.”

She visited Venice for the first time in 1968, arriving early one winter morning after travelling by rail from Rome overnight. “I walked down the steps of the train station and the city whammed me,” she remembers. “I’d seen movies, photos in my geography book, but nothing prepared me for it.”

She made Venetian friends, and returned at least once a year, fitting the visits around a series of teaching jobs in far-flung posts. In Iran, she taught helicopter pilots to speak English (“ ’My name is Ahmed. I am a pilot.’ It was so bo-o-o-r-ing”). In Saudi Arabia, where she lectured in English literature, being female meant being treated as a second-class citizen. She hated the place. “And I hate it still,” she says. “I cannot abide that everybody from the West, because they are oil-rich, sucks up to them.”

By 1981, when she was almost 40, Leon was ready to settle down. Venice was where she wanted to live, and landing the position with the University of Maryland made it financially possible to do so: she taught US servicemen and women at nearby military bases until the income from her books allowed her to retire.

Over time, she has become deeply disillusioned by Italy’s graft-ridden, dysfunctional political and economic systems. “Living here maddens me every day,” she says.

But there are compensations, and she was reminded of them when a tram on which she was travelling in Amsterdam a few years ago stopped suddenly, throwing her onto the floor. “I stood up and looked around, and the tram was full of people who couldn’t have cared less if my head had fallen off when I fell over.” She knew that if it had been an Italian tram, the response would have been different.

“In Italy, there is still a strong impulse to help the person in difficulty,” she says. “The farther south you go, the stronger is the impulse. So if this had happened in Naples, or Palermo, there would have been screams at the driver: ‘What did you do?’ There would have been a competition to help me to my feet. Somebody would have asked me if I needed a glass of water. Nineteen people would have offered me their seats to lie down on.”

Even in northern Italy, she says, “I’m always struck by the warmth and humanity of the people.” For instance, despite Venetians’ understandably mixed feelings about tourists, most seem to do their best to be good hosts, Leon says. “They see someone hopelessly lost, looking at a map, they’ll stop and say, ‘Can I help you?’ ” She does this herself occasionally. She just wishes that “the ships from hell”, as she calls the enormous passenger vessels that cruise into Venice, would stop spewing out 4000 day-trippers at a time.

In 2014, the Italian government moved to prevent the biggest of the ships from entering Venice, but the ban was lifted in early 2015. Last June, the city’s mayoral election was won by Luigi Brugnaro, a businessman who is a strong supporter of the cruise industry. Leon despairs, and the World Monuments Fund has identified the city as a cultural heritage site under threat, saying that “the advent in the last decade of large-scale cruise-ship tourism is pushing Venice to an environmental tipping point and undermining the quality of life for its citizens. Such tourism has increased in the city by 400 per cent in the past five years alone, with some 20,000 visitors per day during the peak season.”

Toni Sepeda tells me the cruise ship passengers who take her Brunetti tours are pleasant enough, “Well, 99 per cent of them.” One of her recent groups included two spectacularly obese Americans who, when they got to the Rialto bridge, said they could not walk over it. Sepeda pointed out that they had signed up for a walking tour. “They said, ‘Well, we can’t do it.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to put you right here in this nice little cafe at the foot of the Rialto on the Grand Canal, and order you some drinks.’ ”

The feeling that tourists are lowering the tone of the place, and trampling it to death, is not new. “Though there are some disagreeable things in Venice,” the American author Henry James wrote in 1882, “there is nothing so disagreeable as the visitors.”

At the same time, the travellers who have flocked to the city for centuries have been a vital source of income for its residents. Jan Morris argues that since Napoleon’s 1797 defeat of the once-great republic known as La Serenissima, “she has been chiefly a museum, through whose clicking turnstiles the armies of tourism endlessly pass”.

The fragility of Venice has always been part of its allure. Here is a city built atop wooden posts driven into the muddy floor of a lagoon. It has been slowly sinking since records have been kept. But scientists say climate change is accelerating the pace at which the water is rising: the mean level in the lagoon is 30 centimetres above the level recorded in 1897, and there are increasing incidences of acqua alta, or “high water”, when a mix of tides and winds causes flooding of shops and houses. Twelve years ago, construction began of a massive flood protection barrier – a system of hollow gates designed to swing up on hinges and create a temporary sea wall when needed.

The project is due for completion this year, but it is billions of Euro over budget and the subject of a major corruption scandal. By late 2014, there were 35 public officials and contractors under house arrest or in detention. “Like an oil slick, it spread out to the various people who were involved,” Leon says. “And, as the investigation was spreading, so too were reports of various engineering problems. I don’t know anybody who thinks this thing will work,” she adds glumly. “This is the kind of swamp in which the city finds itself.”

Music is a source of consolation to Leon. “I can’t sing,” she says. “And I can’t read music. I just like it. Particularly baroque music. Particularly baroque vocal music.” The operas of Handel are her idea of heaven. With the money earned from her books, she has supported two European opera orchestras, Il Complesso Barocco and Il Pomo d’Oro. Besides providing funds, she travels to performances, writes program notes and organises recordings. As far as she is concerned, this is her most important work. “I’m not particularly proud of the books. I’m much prouder of the music.”

She continues to get a kick out of researching and writing the Brunetti stories, though. The newest one concerns bee-keepers who have hives on islands in the lagoon. “It’s going very well,” she tells me. “I’m writing 10 pages a day, which is a lot for a novel.”

Venice still seems to her an unbeatable setting for a detective series. An unbeatable setting, full-stop. She and Brunetti may both gripe about what is happening to the city, but that is only because they love it so much. “Where else in the world is everything you look at beautiful?” Leon asks.

——

Donna Leon in Venice, where her crime novels are set. Photo: Gaby Gerster/Diogenes Verlag AG Zurich