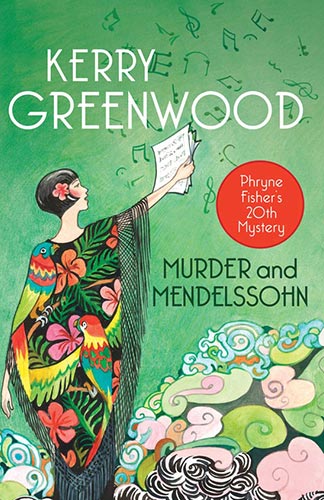

P.D. James once happily observed that Inspector Dalgliesh inevitably resembled Roy Marsden after the actor first embodied her poet/philosopher hero. Ian Rankin, on the other hand, recalled getting rather drunk on a transnational trip to Australia after watching actor John Hannah, who had just optioned Rebus, in The Mummy during the in-flight entertainment. Hannah was simply not the type of Rebus Rankin had in mind when he created his dour detective. Fortunately, Kerry Greenwood, had some say in the choice of Essie Davis to portray Phryne Fisher and the actress certainly looks the part, from her ‘neat bob’ as ‘shiny as patent leather’ to her well-turned ankles.

However, when it comes to the difference between what we will see on the screen and read between the pages of Murder with Mendelssohn, Greenwood’s twentieth crime novel to feature Phryne, there are some significant differences. For example, there is sex scene in the book which is highly unlikely to make it onto the television screen, except perhaps in an R-rated cable version. It involves one hitherto ‘frigid’ gay man, one (arguably) bi-sexual male, and the mischievous Phryne.

While Phryne’s libido has always been voracious, on television she is routinely accompanied by the buttoned-down Detective Jack Robinson in a flirtatious relationship which can only work as long as it is unconsummated. On TV UnResolved Sexual Tension rules: in fiction consummation is, in Phryne’s case, both necessary and frequent.

This is where the screen Phryne and the book Phryne part company. The TV Phryne is a flirt: the literary Phryne follows through and has her man, whoever that might be, exactly as she chooses. As a consequence, Phryne’s erotic adventures are as much a part of her literary career as the cases she solves.

There are, of course, many other pleasures to be had. Like Dorothy L. Sayers, who famously regaled her readers with a treatise on campanology in The Nine Tailors, Greenwood is not averse to some well placed arcane knowledge; this time it’s mathematics and music.

Murder with Mendelssohn includes the demise of an orchestral conductor who has been stifled with ‘quite a lot of sheets of Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah stuffed down his throat’. Not surprisingly, suspicion falls on the members of the amateur Melbourne Harmony Choir who are about to perform the piece. Phryne’s investigation thus affords Greenwood ample opportunity to regale her readers with the inner workings of such choirs, their warm-up routines, their petty rivalries, as well as a just how Elijah should be performed. The dead conductor, it would appear, was murdering Mendelssohn.

Meanwhile, Phryne encounters an old flame, Dr John Wilson, from her years as an ambulance driver in the first world war. Wilson is in Melbourne accompanying the brilliant but arrogant mathematician and ‘shark’ of a code breaker, Rupert Sheffield. The latter is in Australia to give a lecture, but appears to be the target of an assassination attempt linked in some way to his past in the British intelligence.

There’s a nice moment when Sheffield and Phryne first meet as both perform their science of deduction according to Sherlock Homes. ‘Apart from the fact that you are wealthy, have a black cat in the house, use Jicky [Phryne’s favoutrite French perfume] and have slightly sprained your ankles dancing, I know little about you’ Sheffield notes with supercilious satisfaction. Phyrne, never one to be outdone, responds in withering kind. Onlooker John Wilson is amused. The brilliant Rupert Sheffield, he notes, may just have met his match. And so he has.

Like her heroine, Greenwood has never been more confident and confronting leading to the cheering conclusion that while we might applaud TV Phryne’s onscreen triumphs, the Phryne of the fiction is dancing to her own inimitable tune.