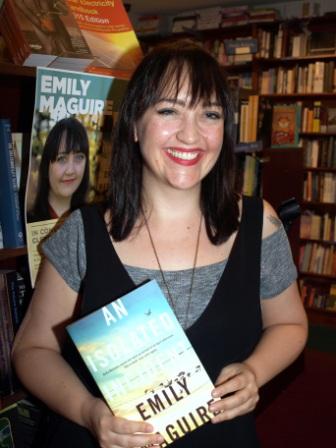

Q&A. Emily talks to Robyn Walton, a national co-convenor of Sisters in Crime Australia, about her novel An Isolated Incident (Picador, March 2016), her first foray into crime.

Hi Emily and thanks for your time.

An Isolated Incident explores the aftermath of the vicious killing of a woman, Bella, with the focus often on the intensely felt reactions of the person who loved Bella most, her sister Chris. Let’s start by talking about Chris, and then I’ll ask some broader questions about your book’s themes and creation.

Sex, male attention, having a warm body beside her in bed: all are very important for Chris, but don’t seem to have played such an obvious part in Bella’s life. Novice reporter May is hurting from the recent break-down of a relationship and is having casual sex with a local womaniser. Any comments about women’s differing needs, wants and ways of seeking intimacy?

I don’t think it’s possible to generalise about women and intimacy in terms of needs and wants. But I do think that there’s something common to many women who are sexually and romantically attracted to men, and that’s the dissonance of wholeheartedly and bodily embracing men when we’ve been warned since childhood about what they’re capable of, and continue to get reminders all the time. Of course we all know it’s a minority of men who do these things, but we have no way of knowing, at the outset, who they are.

May, Chris, and in a more low-key way, Bella, do what many women do. They take leaps of faith in seeking to satisfy their emotional and physical desires. They’re not ignorant of the risks; they simply refuse to go through life feeling like prey.

In your novel Fishing for Tigers (2012) you mentioned the Vietnamese tale of Kiều, a beautiful, kind and smart young woman who lived a tough life, including resorting to prostitution to help her family. I wondered whether Chris is a version of Kiều?

I don’t think so. Kiều’s story is one of self-sacrifice, of filial duty and obligation. Chris is an accidental but willing sex worker. She’s having a good time in bed with truckies who pass through town and is presented with an opportunity to make a bit of extra cash on the side. There’s no sense that she has to take those men home with her or that she’ll be letting anyone down if she stops.

Chris’ loved ex-husband Nate gives her support and protection, but his reciprocal affection has its limits and his propensity for violence is scary. Is Nate your average bloke, a mix of good and not-so-good qualities, or would you prefer not to generalise?

I don’t think it’s possible to generalise. I don’t think the ‘average bloke’ exists, any more than the average woman does. In Nate’s case, there are certain stereotypes about maleness and masculinity that he conforms to and plays up to for better and worse. He’s a large, physically strong man and that is something which is highly valued in terms of traditional ideas of masculinity. He is, in many ways, a classic old-school male protector who can and will stand between those he loves and harm. The problem for Chris is not only the fear of being on the wrong side of his anger, but that seeing him inflict his anger on others – however ‘deserving’ – can’t be unseen. The more she feels unsafe in the world, the more frightening any performance of physical strength and violence becomes to her and so the protector comes to seem like part of the threat.

Chris has a go at stalking one of the men she suspects of Bella’s killing. It doesn’t turn out well. Dark humour?

Chris is a trusting person, very open, not used to being suspicious or sneaky or thinking the worst. Her sister’s murder doesn’t just shake her with grief and loss; it forces her to view the world and everyone in it in a way that is completely new. She’s grieving and rage-filled as well as inexperienced so it’s no surprise her vaguely-conceived vigilantism ends badly. There is humour in it, I think, and it’s rooted in the fact that she is, for all her flaws, a good person. She’s just so ill-suited to this kind of thing.

Now some wider-ranging questions.

Almost all of the action takes place in the southern NSW town of Strathdee. Why a small truck-stop town for your setting?

When a terrible crime occurs, people are desperate to believe that an outsider must have committed it, because otherwise it means there’s a ‘monster’ amongst them and that’s too awful to contemplate. This dynamic is clear in a small country town because everybody knows (or knows someone who knows) everybody else, but the psychological truth holds whether you’re in country, city or suburbia, violence is an everyday event but to admit it’s ‘our’ men committing it is too horrifying and so we search for monsters from outside.

Almost all of the action takes place in the month of April 2015, with the early activity related day by day. Why April? And, bearing in mind you mention some past atrocities, why a contemporary timeframe?

In earlier drafts the time of year varies enormously. I had scenes unfolding in the stifling heat and during frosty winter mornings. I ended up going with April because it tends to be free of the extremes. You get these gorgeous warm, dry days all blue skies and gentle breezes. In the moments before she’s abducted, Bella would’ve felt so safe and calm and good about the world making the short walk from work to car in this perfect weather.

As for the contemporary timeframe, this is a story that is, in part, about what it is to be a woman right now. The unprecedented freedom undercut constantly, though not always visibly, by violence or the threat of violence. The past atrocities are important though. Dig not very deeply at all into the history of any town in this country and you’ll find acts of terrible violence. We should be horrified at how much violence simmers under the surface of everyday life, but we shouldn’t be surprised. It’s been there all along.

Your title echoes the language of those calming police announcements: such-and-such an attack was merely “an isolated incident”. Yet the narrative seems to assert that no act of sexualised violence against a woman can be regarded as unconnected. So your title is ironic?

It’s absolutely ironic. I hope it sticks in people’s heads and that they begin to notice how many ‘isolated incidents’ occur in this country and how similar they actually are to each other.

For older readers in east-coast Australia the name Anita Cobby recalls a reportedly horrifying rape-murder by a group of men. I understand you were a schoolgirl in western Sydney when that killing happened in 1986. Did reactions to that ‘incident’ influence you at all when you began devising this book?

Part of what drove me to write this was rage at the way deaths of attractive young women are fetishised and put into service to sell books and newspapers, and so it was very important to me to not do that myself. For that reason, I very deliberately didn’t draw on a particular real life crime when writing about what happens to Bella.

But certainly, my awareness of how violence against women is reported and responded to in wider society started with Anita Cobby and Janine Balding. I was ten, eleven, twelve when the most gruesome and graphic details of what happened to those women were daily news, daily conversation fodder. I knew the most horrific things about what was done to each of them and yet so, so little about whom these women were. Their names became incantations used to warn us girls about staying out late or going out alone. I felt – feel still – enraged that the names of these women, and others, conjure up images of horror and fear and can be so easily used to scare and control other girls and women.

A city-based feminist coalition proposes honouring Bella’s memory by marching to protest victim-blaming and violence against women. Chris refuses to participate. Did you as author want to take sides re the rights and wrongs of such activism?

There’s an uncomfortable space between linking tragic deaths of women, turning them into a political cause and honouring the individuality of the woman lost and those who loved her. It is gross and cynical to appropriate a woman’s life and death this way, but at the same time, it is necessary to link the deaths of individuals and to speak out about them in terms of a collective, societal problem. If we don’t do that, we have isolated incident after isolated incident and no action, no change. So it’s tricky and uncomfortable and I wanted to capture that in the novel, just let it play out in all its complexity and discomfort.

Hauntings and eerie presences slip into your narrative quite often. Did you plan that?

Not at the outset, but fairly early in the process of writing the novel it started to feel right. Chris is mad with grief, as well as being a heavy drinker, so her perspective is unreliable but there’s no question that she feels haunted and I wanted to let that experience in. I, too, began to feel profoundly haunted while I was writing the novel – constantly remembering and thinking about all these murdered women I’d read about. It was inevitable that some of that feeling would seep into the novel.

Grief is not ‘life-ending’, although it can feel ‘unsurvivable’. Does An Isolated Incident offer readers hope and affirmation (we can have loving partners and trustworthy police, say) or is it more inclined to counsel us to support each other through this complicated, messy existence?

It’s not for me to say what kind of experience the novel will be for readers. For me, in writing it, I got through the darker moments by revelling in the company of the women whose voices I was channelling – Chris and May. In fiction, as in life, the company of tough, smart, complicated, funny and fun women makes the hard stuff easier to bear.

Thanks for your responses, Emily.