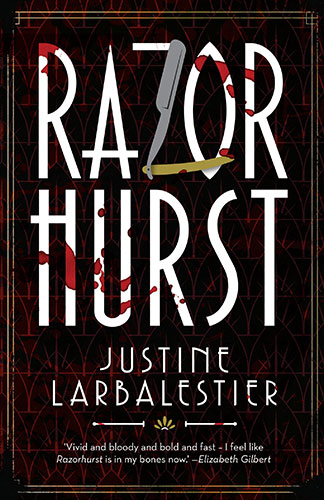

Author: Justine Larbalestier

Publisher: Allen and Unwin

Copyright Year: 2014

Review By: Angela Savage

Book Synopsis:

Kelpie and Dymphna are accustomed to the mean streets of 1930s Sydney, but this is a day that will test their courage, their loyalty, and their ability to survive both the ill-intentions of the living and the ever-presence of the dead.

The setting: 1932, Razorhurst. Two competing mob bosses – Gloriana Nelson and Mr Davidson – have reached a fragile peace.

Kelpie knows the dangers of the Sydney streets. Ghosts have kept her alive, steering her to food and safety, but they are also her torment.

Dymphna is Gloriana Nelson’s ‘best girl’. She knows the highs and lows of life, but she doesn’t know what this day has in store for her.

When Dymphna meets Kelpie over the corpse of Jimmy Palmer, Dymphna’s latest boyfriend, she pronounces herself Kelpie’s new protector. But Dymphna’s life is in danger too and she needs an ally. And while Jimmy’s ghost wants to help, the dead cannot protect the living.

Gloriana Nelson’s kingdom is crumbling and Mr Davidson is determined to have all of Razorhurst – including Dymphna. As loyalties shift and betrayal threatens at every turn, Dymphna and Kelpie are determined to survive what is becoming a day with a high body count.

‘Vivid and bloody an

It’s a long time since reading a novel has made me gasp out loud, but it happened with Justine Larbalestier’s Razorhurst, a gripping, bloody, at times heartbreaking novel, set in Sydney’s inner east in 1932.

The term ‘Razorhurst’, as Larbalestier notes in the ‘Acknowledgements & Influences’ section at the end of the book, was coined and deployed by journalists at the whimsically named Truth newspaper, to describe a culture as much as a place in 1920s and ’30s Sydney, where razor-wielding criminal gangs waged war for control of trades in sly grog, illegal drugs, prostitution, gambling and extortion. The era, and particularly its infamous vice queens, entered the contemporary consciousness through Larry Writer’s award-winning non-fiction work, Razor: Tilly Devine, Kate Leigh and the razor gangs, and the TV show, Underbelly: Razor, that it spawned.

While Larbalestier cites Writer’s book among her influences, together with Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South, and Kylie Tennant’s Fouveaux, Razorhurst, as she describes it, is a ‘wholly imaginary book’ that manages to be thrilling, informative and moving all at once.

The narrative point of view in Razorhurst alternates between Kelpie, a Surry Hills street kid of indeterminate age who sees ghosts and, as she muses, hasn’t been looked after by the living in some time; and Dymphna Campbell, ‘best girl’ of local mob boss Gloriana (Glory) Nelson. The novel opens with Kelpie and Dymphna meeting over the bloody corpse of Jimmy Palmer, Dymphna’s erstwhile lover and Glory’s top standover man. The key suspect behind Palmer’s death is Glory’s arch rival Mr Davidson.

What unfolds over the following twenty-four hours makes up the novel’s intense and compelling narrative, as Dymphna takes Kelpie under her wing, and both young women struggle to distinguish friend from foe and survive the night.

Kelpie and Dymphna’s narratives are interspersed with short, sharp (no pun intended) chapters about minor characters, settings and vignettes — e.g ‘Standover Man’, ‘Kelpie’s Theories of Ghosts’, ‘Gloriana Nelson’s Doctor’ — that add colour and depth without sacrificing pace. Somehow Larbalestier manages to balance a light authorial touch, while conveying a substantial amount of information and nuance.

But the novel’s emotional punch comes from its characters: Kelpie and Dymphna are wonderfully rounded and convincing; but also engaging are writer and brewery work Neal Darcy; Mr Davidson’s Aboriginal standover man Snowy Fullerton; Old Ma, Kelpie’s esrtwhile carer; and Miss Lee, who taught Kelpie to read — not to mention Glory, Mr Davidson, and their respective entourages.

Also worth noting is that the violence in Razorhurst, while bloody and vivid, is neither gratuitous nor glamorous (unlike the violence in the Underbelly TV franchise). The consequences of violence are shown to be brutal and heartbreaking. In a short chapter called ‘Funerals’, for example, Larbalestier writes:

“Hard to come back from burying your own child. They should not die before you. Parents die first, then children. That’s the natural order of things. Not in the Hills though. Not always. Sometimes it felt like not ever.

Flowers and a coffin and a nice little burial suit did not to a thing to ease the ache in your heart. That’s what the alcohol was for.

That and to put you a few steps closer to your own grave. Why live once your children were gone?”

Razorhurst has won awards as Young Adult fiction for Older Readers, although I could see little to distinguish it from an adult read, apart from (possibly) the age of the main protagonists. Highly recommended.

This review first appeared on Angela Savage’s blogsite https://angelasavage.wordpress.com/