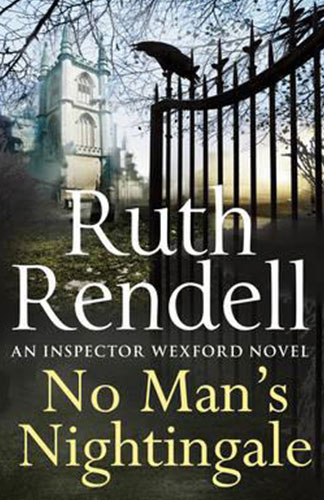

Author: Ruth Rendall

Publisher: Hutchinson

Copyright Year: 2013

ISBN: 978-0-09-195385-0

Review By: Susan Woldenberg Butler

Book Synopsis:

A female vicar named Sarah Hussein is discovered strangled in her Kingsmarkham vicarage. Maxine, the gossipy cleaning woman who discovers her body, happens to also be in the employ of retired Chief Inspector Wexford and his wife. When called on by his old deputy, detective inspector Mike Burden, Wexford, intrigued by the unusual circumstances of the murder, leaps at the chance to tag along with the investigators.

A single mother to a teenage girl, Hussein was a woman working in a male-dominated profession. Moreover, she was of mixed race and working to modernize the church. Could racism or sexism have played a factor in her murder?

As Wexford searches the Vicar’s house, he sees a book on her bedside table. Inside the book is a letter serving as a bookmark. Without thinking much, Wexford puts it into his pocket. Wexford soon realizes he has made a grave error in removing a piece of valuable evidence from the scene without telling anybody. Yet what he finds inside begins to illuminate the murky past of Hussein. Is there more to her than meets the eye?

Inspector Wexford returns for the second time since his 2009 retirement. This is the 24th book in the series that began with From Doon with Death in 1964. Now Wex has to find the murderer of Irish-Indian Sarah Hussain, Kingsmarkham’s first female and Asian vicar, who has been strangled from the front. His police department successor pulls the retiree from his conservatory armchair and The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire — which Rendell quotes lavishly — and the malapropisms of a garrulous cleaner who ‘does’ for him and his wife, Dora, twice a week.

This is another of what Rendell calls ‘the political Wexfords’ concerning subjects she cares about, such as racism (Simisola) and domestic violence (Harm Done). What’s wrong with a mixed-parentage lady ecclesiastic who dresses stylishly?

Characters range from deliciously non-politically correct to suffocatingly earnest. Suspects include the church gardener; the same-sex partner of the vicar’s late husband’s brother; a reactionary male deacon; a wannabe property mogul who illegally sublets his ex-girlfriend’s council flat; and a fabulist — read liar — and her plain-speaking husband —or is it the other way round?

Rendell covers a lot of territory, weaving more than one strand into her story fabric. One subplot is Sarah Hussain’s orphaned teenaged daughter’s search for her father, with the exploration of father-child relationships crucial to the denouement. Rendell utilises a particularly attractive plot device: ruminations on why people chose the Christian names and surnames they do for personal aliases and for their children.

You could anticipate settling in for the latest by the best, and you would not be disappointed. We catch up with an old friend and familiar rhythms, while simultaneously being nudged into the present-day as Rendell forces her old detective chief inspector to move with the times. For example, he says ‘It’s the way we live now’ when suggesting that a junior police constable known as Lynn call him by his Christian name instead of ‘sir.’ He punctiliously reveals that he is no longer a policeman to every interviewee. He is also very aware of the passage of time. He naps regularly and comments frequently on such intergenerational differences as the use of sherry by older generations. ‘They each had a glass of sherry, that drink that Clarissa and Robin and their contemporaries had never heard of.’ Additionally, his sceptical successor, at the mercy of a lurking press, hasn’t touched the bottle of Amontillado sherry Wex left on his office shelf on the last day. Our old friend also repeats himself, for example with this observation and variants: ‘If he was no longer a police officer, he had recently been one, a detective chief inspector, and for many years.’ Last, Inspector Wexford is more tentative. Rendell intersperses an exploration of the psychological effects of ageing and retirement on one of society’s most productive members, exemplified by frequent references to loss of status and position, and word and dress usage by the younger generation(s).

One quibble: the use of ‘Hussain’ as an Indian Hindu name is incorrect. Rendell stressed this cultural and religious heritage for the late vicar. Muslims use ‘Hussain’ as both Christian and surnames. An Indian so named would be from the northwest of the country, near Pakistan and Kashmir, and would be Muslim, not Hindu. We don’t know the nature of Rendell’s editorial agreement with her publisher, but a knowledgeable, literate fiction editor would never have let this slip by. Taking a course and tacking a profession to one’s LinkedIn skills set are insufficient. Despite this, this misuse is not enough to ruin a good Rendell, especially in her continuation of the tradition of Christie’s Murder in the Vicarage. It’s a delight.